Modernist architecture: inspiration from across the globe

Modernist architecture has had a tremendous influence on today’s built environment, making these midcentury marvels some of the most closely studied 20th-century buildings; check back soon for new additions to our list

Modernist architecture defined the 20th century like no other movement. Its midcentury marvels quickly spread across the globe, represented in a multitude of typologies, scales and geographical locations – and giving birth to just as many regional expressions. Some of the 20th century’s most well-known architects – Le Corbusier, Mies van der Rohe, Balkrishna Doshi, Oscar Niemeyer, Lina Bo Bardi, Eileen Gray, Tadao Ando, Frank Lloyd Wright, Adolf Loos, Louis Kahn, to name but a few – are intrinsically linked to it. It is a movement with countless faces, and one that still influences design and architecture like no other. Here, in an evergrowing round-up to celebrate, study and be inspired by its gems, we tour some of the world's finest examples of modernist architecture.

THE WORLD'S FINEST MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE

Ahm House by Coppin Dockray

Danish structural engineer Povl Ahm worked on some extraordinary projects in his lifetime. After joining the London office of Ove Arup & Partners in 1952, he collaborated on Coventry Cathedral with Basil Spence and St Catherine’s College in Oxford with his countryman Arne Jacobsen; later the pair worked together again on the Danish Embassy in London. One of Ahm’s greatest, though lesser known, achievements is his own house in Harpenden, Hertfordshire, which has won a Wallpaper* Design Award for Best Remastered. Ahm built an exceptional home designed by Danish architect Jørn Utzon, whom he got to know during the early design stages of Utzon’s Sydney Opera House, which also involved Ove Arup & Partners. Ahm asked Utzon to design a house in England and the architect obliged, sending his plans over in the early 1960s for his friend to work with.

The original Ahm House – Utzon’s only completed project in the UK – was gently pushed widthways into the modestly sloping suburban site. From the street, the house is enigmatic, with the garage and entrance forming a buffer between the public and private realm. But as you step inside the entrance hall and ascend a series of steps, Ahm’s pavilion dramatically unfolds. This linear lodge of brick, concrete and glass turns its back upon the neighbours to one side but opens itself dramatically to the rear gardens.

St Anne’s Close by Walter Segal and Hayatsu Architects

Set in Highgate, north London, St Anne’s Close was developed by architect Walter Segal in 1952, as a private housing co-op for himself and a group of friends. The result was a series of eight clean and elegant brick homes on stepped terraces. One of them is a detached property, and the owners recently called upon Hayatsu to mastermind a refresh and rear extension to accommodate the growing needs of their young family.

The 145 sq m of floor space added with this project contains a new kitchen, a multipurpose sitting room, shower room and a bedroom at the rear of the property, stretching out into a leafy garden. Simple lines, a fairly straightforward brick volume, and a low profile ensure the new element does not distract from the original design’s identity. Its flat roof is planted with wildflowers and moss, to blend easily with the surrounding nature. An oak trellis and pergola frame the landscape and will turn greener as vegetation grows.

Lubetkin tower apartment in London by Studio Naama

A Lubetkin tower apartment in east London has been given a 21st-century makeover by emerging architecture practice Studio Naama. The small, but dynamic firm, led by co-founders Mark Rist and Natalie Savva, completely transformed the apartment interior design to fit the specific needs of their clients, a pair of keen cyclists, while maintaining the modernist architecture's bones and Bertold Lubetkin's original intention. So successful was the space's reimagining that it won the duo an award (Compact Design) at the Don't Move, Improve 2023 competition earlier in the summer. Set within Lubetkin’s Grade II listed Sivill House on Columbia Road, Shoreditch, the apartment was originally designed by Lubetkin together with Douglas Bailey and Francis Skinner in 1962. Preserving the space's modernist legacy was key to the two architects. At the same time, within a modest 65 sq m, the clients wanted to make the most of their two-bedroom property.

Hampstead House by Trevor Dannatt and Coppin Dockray

Saved from possible demolition, a post-war Hampstead house designed by titan of British modernism, Trevor Dannatt, has had years of piecemeal additions peeled back in a refurbishment for a young, growing family. Coppin Dockray, an architecture studio familiar with employing historical sensitivity in its delicate revivals of 20th-century buildings, strikes a meticulous balance of preserving the house’s original character while infusing contemporary boldness and resilience in the new design. As a result, this is a versatile, unobtrusive, modern Hampstead house, cradled between grand Edwardian terraces and towering oaks.

Wright and Like Tour 2023 in Milwaukee

It's almost time for the Wright and Like Tour 2023 in Milwaukee. For the second time following its pandemic-induced two-year pause in 2020 and 2021, the Wright in Wisconsin organization is sponsoring its popular tour event, set to take place on 29 July 2023. Now in its 24th year overall, the tour features homes and other structures located in and around Milwaukee, specifically the communities of Bayside, Fox Point, River Hills and Shorewood - and it is all curated to celebrate and appreciate the work of 20th century modernist architecture master, Frank Lloyd Wright. While, the 'Wright' part of the tour may feel self-explanatory, given the event's overall theme, the 'Like' part is more unusual. It is a section of the tour that refers to homes and structures related to the work of Frank Lloyd Wright, but designed by other architects. Most of the 'Like' sites for this year’s tour are Usonian in design and concept; one of them this year, for example, is a 21st century interpretation of the mid-century modernist style. This combination ensures a broad mixture of visits for the tour, according to Wright in Wisconsin representative, Bill Swan.

Architecture and Design Center – Palm Springs Art Museum, by E. Stewart Williams in 1960 and renovated by Marmol Radziner in 2014

It’s hard to imagine snow in Palm Springs, but at the Aerial Tramway Mountain Station 2,600m above the town in the San Jacinto Mountains, it’s possible and fairly regular. A refuge for hikers and wildlife lovers, the station designed by architect E. Stewart Williams (1909-2005) is a modernist three-storey chalet with concrete wraparound viewing decks, complete with cosy cocktail lounge with fireplaces and sweeping curved glazed facades overlooking Palm Springs and the valley beyond. Of all the architects who shaped Palm Springs, Williams was the one who shaped public life the most. His legacy can be seen all over town. He’s the architect behind the Palm Springs Art Museum (1976) and the Santa Fe Federal Savings & Loan building (1960), bought by the museum and reopened as the Palm Springs Art Museum Architecture and Design Center in 2014, after a renovation by LA-based practice Marmol Radziner.

Jyvaskyla City Theatre by Alvar Aalto

When Finnish photographer Janne Tuunanen travelled from his base in New York to his home town of Jyvaskyla at the start of the pandemic, his plan was to take some time to slow down and spend the crisis closer to his family there. Soon, he picked up cycling and riding around town he rediscovered, after years of being away, the modernist architecture of Alvar Aalto; this lesser known, sleepy town in the western part of the Finnish Lakeland, is a treasure trove of the master architect's work. ‘I thought there might be material for a bigger project here,' he says. ‘I approached the Alvar Aalto Foundation about the project and they approved my pitch.' Tuunanen went on to create 17 images of Aalto's masterpieces in the vicinity, including the architect's own Experimental House and Jyvaskyla's main theatre, swimming pool hall and the local Museum of Central Finland.

Goldberg House by William Cody

Palm Springs is one of the global epicentres of tasteful big ‘m’ modernism, a sprawling desert city where the dreams of architecture’s new generation came to glorious fruition, usually unrestricted by budgets and the tiresome burden of inclement weather. It was here in the desert that architects could explore the limits of glass and steel to their heart’s content; the resulting spindly paeans to open-plan living brought the arid desert landscape into the heart of the post-war house. Palm Springs continues to bask in its modernist heritage, with an annual celebration of design, exhibitions and open houses and a strong ongoing tradition of innovation architecture. The pioneers who shaped the city included Albert Frey, Lloyd Wright and Richard Neutra, whose Kaufmann House continues to be the defining image of desert modernism. John Porter Clark, Donald Wexler and Richard Harrison and Palmer & Krisel were also prime movers, working hand in hand with property developers and hoteliers to transform Palm Springs into a destination for holidaymakers and weekenders, keen to escape the smog and stress of Los Angeles (the resort started life in the early 20th-century as a health retreat).

In addition to the restrained modern elegance of the post-war era, Palm Springs was also home to eclectic design voices, drawn by both the light and space and the eccentricities of the burgeoning city’s clientele. ‘Desert Modern’ was the result. William F. Cody is one of the style’s prime exponents. Cody came to Palm Springs in 1945 in search of fame and architectural fortune. He had been lured by the formidable Nellie Coffman – ‘The Mother of Palm Springs’ – to extend the Desert Inn, the sanatorium she founded in 1909 and which evolved throughout the century. Cody was just 29, a recent graduate from the College of Architecture and Fine Arts at the University of Southern California (alumni of the era included Paul Revere Williams, Pierre Koenig and William Krisel).

FIDAK (Foire Internationale de Dakar), Dakar, Senegal, designed by Jean Francois Lamoureux and Jean-Louis Marin, 1974

If architecture is, as Mies van der Rohe famously claimed, ‘the will of an epoch translated into space’, how was the break from colonial rule expressed in the built environment? With daring and optimism – at least in the sub-Saharan Africa of the mid-twentieth century, when newly independent African countries were confronting complex issues of sovereignty and national identity. An exhibition organised by the Vitra Design Museum, on view in 2017 at New York’s Center for Architecture, explores this wave of ‘African Modernism’. ‘When the countries of sub-Saharan Africa became independent, the young nations used architecture as a tool for nation building,’ says Manuel Herz, curator of the exhibition and editor of the accompanying book African Modernis’, published by Park Books. ‘I wanted to focus on the countries that became independent in the years between the late 1950s and the early 60s, as I also wanted to focus on architecture of the 1960s and 70s.’ And so the government buildings, museums, schools, universities and conference centres featured in the show are in five budding nations: Ghana, Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Kenya and Zambia.

Racquet Club Cottages West by William Cody

William Cody’s serene group of homes at the Racquet Club Cottages West are a lesser known Palm Springs gem. Los Angeles developer Paul Trousdale worked with Cody to create a quiet modern enclave of 37 homes as an antidote to the celebrity-filled Palm Springs life. Built in 1960, the cottages are immersed in an oasis of palm trees, curved pathways and meandering streams and rarely seen by outsiders. The houses feature exposed beams, thin rooflines, private patios, floor-to-ceiling sliding glass doors, and room service delivered from the nearby Palm Springs Racquet Club.

Essex Modernism, UK

Bishopsfield Estate, Harlow, 2016

Essex, UK is peppered with pioneering and experimental architecture from the early and mid-20th century. These modernist architecture gems have been championed in the past during Essex Architecture Weekend, part of the Radical Essex initiative, which seeks to reevaluate the region in relation to its rich cultural history. Delights include Silver End, the village built by window industrialist Francis Henry Crittall to house his workers. Its village hall is the hub for the two-day event, and houses an exhibition. Other sites of note include the Bata Estate in East Tilbury, founded in 1932 by eponymous shoe company pioneer Czech Tomáš Baťa; and the coastal resort of Frinton-on-Sea. Shuttle buses will carry visitors between these sites.

Lord House by Richard Neutra

When Dora Chi and Erik Amir came across Lord House in 2021, they knew they had struck gold. The Los Angeles home, commissioned by TV writer and composer Stephen Lord in 1961, may have been in a terrible state, all gutted and dilapidated, but the hand and intention of its architect were still present and strong. This was a modernist architecture classic waiting to be revived, an original Richard Neutra design, which the husband and wife team, and co-founders of young architecture studio Spatial Practice, decided to snap up and bring back to life. Lord House sits off Mulholland Drive at the end of a private road, in a lot that provides both seclusion and long views over the Los Angeles hills, with the Santa Monica Mountains and the San Fernando Valley in the distance. The two architects embarked on transforming the neglected structure into their own home, at the same time bringing it back to its former glory, respectfully restoring and sensitively tweaking the midcentury bones for 21st-century living. 'We were captured by the simplicity and purposeful design toward nature by Neutra that made the quality of space so unique,' says Dora Chi. 'Naturally, we were also excited to dive into the world of one of the most influential midcentury architects, Richard Neutra.'

New Century, Manchester

Manchester's celebrated music venue New Century has just reopened following a sensitive retrofit by architects Sheppard Robson. Working with interior designers Sheila Bird Studio, the practice spearheaded an extensive revamp for the iconic nightlife destination, which had lain mostly vacant for years. Now, forming part of Manchester’s city-centre NOMA regeneration project, the modernist architecture of the 1,000-capacity venue is back in action. New Century was originally built in 1963 for the Cooperative Wholesale Society, as part of GS Hay and Gordon Tait's New Century House complex (which included an adjacent high rise). Now, the somewhat Miesian plinth structure, which is Grade II listed, has been rebranded 'New Century' and will operate autonomously. As well as the music venue, the building now houses spaces for Access Creative College, which trains young people for the creative industries, and a food hall.

Butterfly roof house in Palm Springs by Donald Wexler and William Krisel

Designed by Krisel and built by Solterra, this exact replica of a butterfly roof house from the 1950s was built in Palm Springs a few years ago with modern features

Pat Rizzo and his Orchestra up the tempo and the dance floor swells with men in retro casuals and women with red lipstick and Mad Men hairdos. It’s the annual gala benefit at the Canyon Country Club, the big ticket event of Palm Springs Modernism Week, and the glitterati, archi-literati and anyone who likes to party are there (dress code: glamorous country club). Propped up against the bar in a baseball cap and sneakers is 86-year-old Donald Wexler (1926-2015), one of the founding fathers of ‘desert modernism’ and creator of the backbone of Palm Springs – its schools, hospitals, banks and airport – from the 1950s to the 1980s. Wexler is of a generation that includes Albert Frey, E Stewart Williams and William Cody, who based themselves in the tiny desert enclave and turned its dust to diamonds. During Modernism Week, he takes on a god-like status. House owners open up their modernist gems to allow the public a snoop, and Wexler puts in guest appearances at talks, lectures and screenings. He’s loving the limelight that has finally found him. ‘It’s great. I’m fascinated by the number of people who are interested in my work and amazed that people see things in it.’

Helsinki Olympic Stadium

The modernist architecture of the Helsinki Olympic Stadium has recently been given a makeover. The elegant piece of design was originally created in the 1930s, but sadly not used until the Summer Olympic Games of 1952, due to World War II. Now, following a recent, four-year-long renovation by a team of architects including K2S, NRT, White Arkitekter and Wessel de Jonge, the stadium has reopened and has been lovingly documented by New York based photographer Janne Tuunanen in tribute. ‘I found the combination of midcentury architecture and modern design intriguing,' explains the photographer. ‘I thought the renovation of the stadium has been done really well, in terms of keeping the old aesthetic alive. Also the use of wood on the new roof as well as the new seats were pretty impressive.' Indeed, maintaining the spirit of the original architecture was key in the restoration works. As a result, any additions feel organic (and are done mostly underground and out of sight) and the building is functional and feels up-to-date and polished. Yet it still exudes the sense of optimism and experimentation of the early modernist approach.

Originally designed by Finnish modernist architects Yrjö Lindegren and Toivo Jäntti, the stadium features an extra tall, striking tower that has become a Helsinki landmark since its completion in 1938. The architecture blends streamlined concrete forms, sharp, white surfaces and shapes subtly remniscent of ocean liners, in typical fashion of the modernist styles of the time. Now, a new timber clad canopy protects the stalls, while the seats have been replaced by modern versions made of sustainable wood composite.

Fondation CAB

There’s a brand new addition to the exceptional modern and contemporary art circuit in the south of France: the Fondation CAB, located in Saint-Paul-de-Vence. The new foundation is an offshoot of the Brussels non-profit art centre of the same name, dedicated to conceptual and minimalist art. CAB’s founder, businessman Hubert Bonnet, was looking for a second address, and fell for this 1950s-era former art gallery with modernist architecture, sensuous white curves and large bay windows. The French architect Charles Zana renovated the space, adding a travertine reception desk, a bookshop-boutique, four guest rooms, a restaurant, and a lounge where you can flip through art books or just gaze out at artist Richard Long’s circle of white stones in the grass.

The art starts the moment you step through the front door, where Felice Varini has painted an installation of four orange circles. A series of rooms display works from Bonnet’s collection, including Carl Andre, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Donald Judd and Dan Flavin. These are complemented by revolving temporary exhibitions – the opening show, ‘Structures of Radical Will', combines minimalist pieces from the 1960s and 1970s with in situ works by contemporary artists. Zana added four guest rooms to the foundation, each one unique and furnished with vintage 20th century pieces: a Charlotte Perriand table, Jean Prouvé chairs, an Alvar Aalto lamp, and Le Corbusier headboards that also serve as storage space and room separators. Zana says he worked closely with Bonnet on the design: ‘We imagined guest rooms we would like to stay in if we were in the Côte d’Azur.' The pièce de résistance is a 6mx6m demountable Prouvé house, perched between two koi ponds in the garden. Surprisingly, it is available to rent on booking.com (for about €800 a night).

Villa E-1027 by Eileen Gray

Villa E-1027 in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on the French Riviera, an emblem of modernist architecture by Eileen Gray, has just reopened its doors following extensive restoration works. The two-storey house, which was completed in 1929, is a testimony to the vision, flair and expertise of the Irish furniture designer and architect. Contributing to its uniqueness are the sweeping views over the Bay of Monaco, which influenced the site’s nautical references, from the iconic Transat lounger, based on the classic ocean-liner deckchair, to the blue-hued rugs and the balcony with its azure canvas awnings. The villa is further defined by a sense of personal attachment and artistic conflict. The most symbolic is its name, E-1027 (to be pronounced ‘e-ten-two-seven'). ‘E' stands for ‘Eileen', followed by ‘10' for ‘J' (representing ‘Jean'), then ‘2' for ‘B' (‘Badovici') and finally ‘7' for the ‘G' in ‘Gray'. Jean Badovici was a Romanian architect, Gray's then-partner and the owner of the villa. According to Gray, he collaborated with her on the site’s general plan. In the late 1930s, several years after she had left the house, Le Corbusier came and stayed there on Badovici’s invitation and started to paint some of its walls. Upon discovering his mainly primary-coloured murals, which contrast Gray’s subtle palette, she proclaimed that he had ‘defaced' her work. After the passing of Badovici, the house was sold to new owners and in the next years it went through a series of dramas, including the selling of its furniture, being taken over by squatters and even a murder. The emptied and damaged property was left derelict in the 1980s.

Frey House II by Albert Frey

When you look at the low, long and linear forms of Albert Frey's buildings, which appear modern, but also instantly at one with the arid landscape of the USA's Coachella Valley, it is hard to believe that this founding father of Desert Modernism in fact hails from the snowy mountains of Switzerland. Yet a look at Frey's illustrious career at the forefront of his profession, which led him from the heart of European modernism to working for Le Corbusier in Paris and designing buildings in New York, and it becomes clear that his worthy accolades are no accident. Born in Zurich in 1903 and coming from a more traditional, building-orientated academic background – rather than being influenced by the more style led movements of his time, predominantly the Beaux-Arts – Frey worked in his home country and Belgium, before finding a position at Le Corbusier's Paris office. There, he worked on seminal projects with the great master, such as Villa Savoye, together with co-workers of the likes of Josep Lluís Sert and Charlotte Perriand. Frey's career stretched over 60 years and is varied, but some of his residential designs – most notably his own home, Frey House II – probably form his most well known works. Perched on the mountainside, majestically overlooking the city of Palm Springs, just a short drive from the city centre and on the west end of Tahquitz Canyon Way, Frey House II is as iconic a desert house as they get. Completed in 1964 as the architect's second home in the town, the residence is the result of careful calculations of the site's stone-filled topography and the sun's path. Mixing modern materials such as glass and metal, with local stone, Frey composed a compact, steel-framed structure with little impact to the environment. Still, it features key the Palm Springs staples, such as a swimming pool and sun deck.

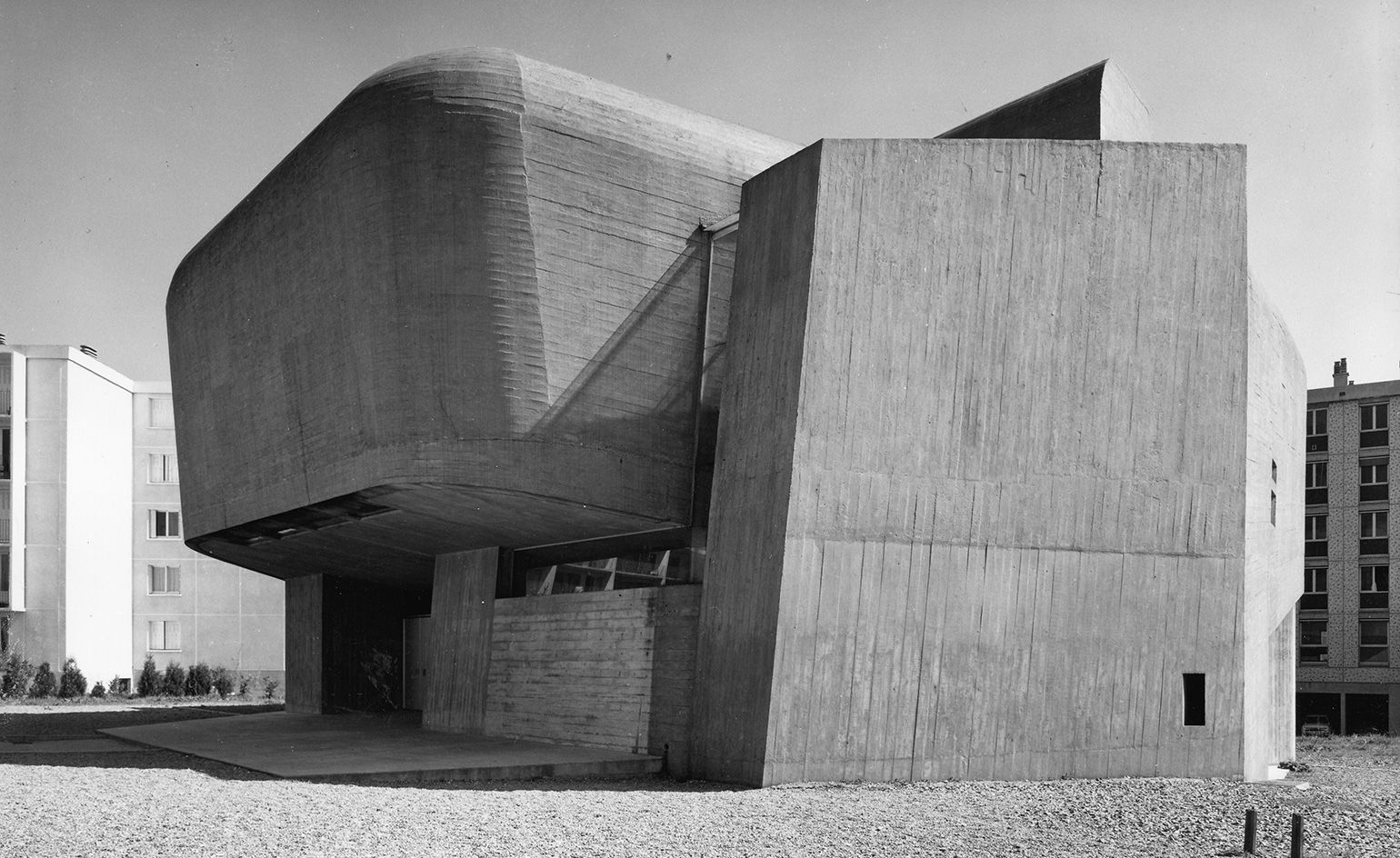

Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay, by Claude Parent and Paul Virilio

The late Claude Parent initially set up with architect Ionel Schein, but it was a decade later, when collaborating with his friend, the urban planner Paul Virilio, that his career took off. Pictured: the church of Sainte-Bernadette du Banlay, by Claude Parent and Paul Virilio, an archetypal example of the duo's fonction oblique. SIAF/Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine/Collection FRAC Centre – Val de Loire

Claude Parent was one of France's most revered modern architects, and in 2005 he was invited to become a member of the Academie des Beaux-Arts. For the inauguration ceremony, he had to dress up in an overblown white bow-tie, embroidered tails with more than an echo of Widow Twanky about them and carry a ninja-style sword that he himself designed. ‘You should have seen me,' he chuckles, ‘the costume was ridiculous, and I had to buy it!' The 204-year-old institution is France's most prestigious arts body and is full of composers, painters, sculptors and a sprinkling of architects, éminences grises all, but Parent stands out from his fellow professionals – Paul Andreu and Roger Taillibert among them – in that he dropped out of Paris's École des Beaux-Arts and so never qualified. Which may explain his unorthodox approach to buildings.

He started out in 1942, a time, he says, ‘that is not remembered for its enthusiasm for architecture', and during his long career, has hung out with all the ‘avant-gardists' of the day. He collaborated with Yves Klein on a series of paintings of a 'petite stripteaser' and the design of some fountains for the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, held a conference on a cliff in Folkestone, England, in 1966 with Peter Cook of anarcho British architects Archigram (‘To our surprise, everyone came!'), and completed a six-month stint at Le Corbusier's studio, something he found less than exciting. ‘He was very much the boss and it was a bit suffocating. But when he was there, you saw his genius, although he never made any money; his buildings took too long and were so expensive,' says Parent.

Cree House by Albert Frey

Cree House is one of the lesser known works by acclaimed California architect Albert Frey. The man behind Palm Springs classics, such as Frey House II, Loewy House and the Tramway Gas Station with its famous ‘flying’ canopy, created this hidden gem around 1955. Having worked with Le Corbusier and influenced by modernist teachings from Europe, Frey worked on this private residence in Cathedral City, which was left neglected for years and fell into disrepair before it got restored to its former glory for Palm Springs Modernism Week 2019. Elements such as the exterior and interior wall panels, the fluted fiberglass deck pieces, kitchen appliances and cabinets have been preserved and remain part of this Desert Modernist house.

Garcia House by John Lautner

Perched nimbly on one side of the Hollywood Hills along Mulholland Drive in Los Angeles, John Lautner’s futuristic Garcia House is one of the most enduring specimens of the midcentury modern movement. Completed in 1962 for the jazz musician, conductor and Hollywood composer Russell Garcia and his wife Gina, the almond-shaped house is as well known for the steel caissons that hoist it 60ft above the canyon below as it is for its part in 1989’s Lethal Weapon 2, where it appears to come crashing down in a foul blow to the film’s villains. Special effects and celebrity aside, the Garcia House, which is, in fact, standing tall and well, now serves as a piece of living history, with its V-shaped supports, parabolic roof and stained-glass windows. The house’s current owners, entertainment business manager John McIlwee and Broadway producer Bill Damaschke, have been on a mission to restore and revive the house since they purchased it in 2002, while living there full time.

Guggenheim New York by Frank Lloyd Wright

Frank Lloyd Wright's Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum is a true icon of modernist architecture, its rounded shape and spirals shorthand for progressive thinking and the 20th century. The building, which opened in New York in 1959, is widely considered its author's masterpiece. It is also part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Since its creation, the Guggenheim has been designated a New York City Landmark and was carefully renovated at the turn of the century - and is now hosting ground breaking exhibitions in art, architecture and design.

Brasilia by Oscar Niemeyer, Roberto Burle Marx, João Filgueiras Lima (Lelé), and more

You don't have to be an architecture expert to have heard of Brasilia. Contemporary Brazil's renowned capital was purpose-built in 1960, featuring a grand urban plan by Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer as its iconic principle architect and Roberto Burle Marx as the landscape designer, plus buildings from some of the country's finest architects. Its urban planning design has been an example and universal reference to architects and urban planners ever since. And it was all beautifully designed in the era's most forward thinking style - the International Style - which Brazil took and made its own. Recently, home to some 2.6 million Brazilians and a listed UNESCO World Heritage Site, Brasilia marked its 50th anniversary; with its famous Niemeyer buildings, and lesser known classic modernist structures like the Sarah Hospital by João Filgueiras Lima (Lelé) and the Nilson Nelson Arena by Ícaro Castro Mello.

Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, better known as Le Corbusier, sits alongside Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe in the reputational VIP lounge of 20th-century architecture. But if Lloyd Wright was the man of the flat prairies, of long horizons and open (mostly domestic) spaces; and Mies, the Bauhausian who bought great glass boxes to meaty, muscly Chicago, redefining corporate architecture in the process; then Le Corbusier is the arch European modernist and master planner, the man who hung out with Fernand Léger and then launched his own post-cubist artistic movement (tagged 'purism'), designed a roomful of iconic furniture – working with Charlotte Perriand and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret – and then plotted high rise living and built a city from scratch at Chandigarh. Along the way, he designed what might be the most beautiful of post-war buildings, the Chapelle Notre Dame du Haut in Ronchamp, France.

Farnsworth House, USA

The Farnsworth House in Plano, Illinois, has been a key site for architecture pilgrims for years, since its creation by Mies van der Rohe in 1945 (and completion in 1951) for Dr Edith Farnsworth. Its clean lines, arresting simplicity and minimalist perfection have inspired architects, designers and artists for generations.

SC Johnson HQ in Racine, USA

Long before Apple and Google hired Norman Foster and Bjarke Ingels to build sexy campuses in Silicon Valley, HF Johnson Jr hired Frank Lloyd Wright to build his Administration Building (1939) and Research Tower (1950), which remain two of the most innovative, and important office buildings in the history of modern architecture. 'I wanted to build the best office building in the world, and the only way to do that was to get the greatest architect in the world,' Johnson explained at the time. The Research Tower, renovated in 2013, was opened to the public for the first time a few years ago. Its 15 floors all cantilever off a central core, which extends more than 50 feet into the ground. The research spaces are skinned with 'Cherokee Red' bricks, and more than 7,000 Pyrex glass tubes. The development site of ubiquitous products like Glade, Pledge, and Raid, the tower contains original lab equipment, amazing architectural drawings, and correspondence between Wright and Johnson.

Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (IIM-A), India

A World Heritage preservation controversy continues to brew. In 2020, the administration at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad (IIM-A) was set to proceed with its plans to raze 14 out of the 18 dormitories in Louis Kahn's modernist architecture complex for the Indian school. A row kicked off as the design community and citizens initiated a campaign against the decision of the management. It got support from global organisations and individuals including Pritzker Prize laureates, the Council of Architecture in India, MoMA, and the World Monuments Fund. Consequently, in January 2021, the management decided to put the demolition on pause – a decision reversed in November 2022, when IIMA director Errol D'Souza announced that some of the buildings would be demolished and reconstructed, citing safety concerns.

In the Americas, Kahn is known for masterpieces, such as the Salk Institute in California, Philips Exeter Academy Library and the Kimbell Art Museum in Texas. In Asia, major works include the National Assembly Building in Dhaka, and the IIM-A campus is widely considered one of his finest contributions. The campus, built between 1962 and 1975, has a distinct modernist sensibility with its geometrical openings and sculptural monolithic brick structures. Brick is matched by concrete bracing elements. Kahn drew inspiration from historical treasures, such as the 15th-century palaces of Mandu in India and the brick cylinders of Albi Cathedral in France.

Sangath, India

Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi is the recipient of the prestigious 2022 Royal Gold Medal for Architecture. The coveted gong was awarded to the established and widely acclaimed Indian architect through the RIBA and by personal approval by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth – it is the UK’s highest architectural honour, announced annually and celebrated around the world by the architecture and design field. Balkrishna Doshi, who also won the 2018 Pritzker Prize and was interviewed in his Ahmedabad home by Wallpaper* in 2009, is one of the world’s most respected architects in his field. Pictured above is the architect’s own studio, Sangath, in Ahmedabad, India.

Yale Center for British Art, USA

Louis Kahn’s masterful Yale Center for British Art recently re-opened its doors after the completion of a $33 million, eight-year renovation led by New Haven-based Knight Architecture. The five-story 1974 building houses the largest collection of British art outside of the United Kingdom, donated in 1966 by Yale Alumnus Paul Mellon. Its intimate, naturally lit galleries are organised around two ethereal interior courtyards, floored in travertine and clad with grids of bare concrete, matte steel and white oak wall panels. Perhaps most famous for its monolithic anchor piece, a drum-like cylindrical grey cement staircase, the centre is an astonishing example of Kahn’s gift for eliciting visceral emotion through pure volume, light, and materials.

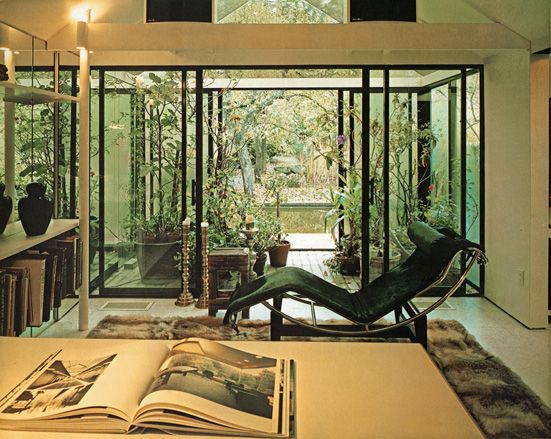

Arthur Erickson house, Canada

The late great Arthur Erickson, Canada's most renowned architect, was a jet setter and a world traveller. He had an impressive list of international clients and hobnobbed with the likes of Pierre Trudeau, Margot Fonteyn and the British Royal Family. But the place in his native Vancouver he called home – recently under threat unless sufficient funds are raised to ensure its restoration – was a relatively understated abode in a bucolic, residential neighbourhood, where raccoons and sparrows were just as likely to turn up as any grander visitors. A converted garage on a double lot he purchased in 1957, and transformed into an elegantly executed contemplative space, it was really more of an appendage to his rather extraordinary garden. Although his garden parties were legendary, 4195 West 14th Avenue was above all a sanctuary for Erickson, who would return from LA or Baghdad and stay cocooned in his small green paradise, contemplating his next project.

Chandigarh’s Capitol Complex, India

The Capitol Complex in Chandigarh, India, is considered as one of the most significant pieces of Le Corbusier’s realised body of works, commissioned in the course of what he referred to as ‘patient research’. It demonstrates Le Corbu's ‘five points’ as well as the ideas of the Ville Radieuse and Athens Charter that encapsulate his practice ideology. The Capitol Complex includes three buildings – the Punjab and Haryana High Court, the Palace of Assembly, and the Secretariat, as well as the Open Hand Monument, interspersed with water bodies and a few other smaller structures. Chandigarh was conceived in 1951 as the new capital of the state of Punjab, after the 1947 partition that led to the creation of Pakistan. Its coveted Unesco status brings with it a renewed energy for the city, to conserve its exposed concrete edifices, as well as to expand and evolve the narrative of its modernist legacy, to resonate with the idea of contemporary India.

Barcelona Pavilion, Spain

It’s been more than three decades since the recreation of Mies van der Rohe's feted Barcelona Pavilion. Designed in 1929 for the Barcelona International Exhibition, the beautifully refined glass, steel and marble structure was quickly disassembled in 1930. Half a century passed with only photographs and drawings for reference; but though long gone, the structure was not forgotten, fondly remembered by the world as a shining example of Mies van der Rohe’s architectural genius and 20th-century modernism. Work began in 1983 to reconstruct the iconic building on its original site, with the Pavilion finally reaching completion in 1986.

MUBE museum, Brazil

Paulo Mendes da Rocha died in 2021. But when Wallpaper* interviewed him in 2010, as this extract shows, he was still channelling the energy of a revolutionary at the age of 81:

The architect’s discourse, usually self-contradictory, is intense, much like the body of work that spans his 50-year career. Take his house in Butantã, for example, which he built in 1964. Even today, it’s an architectural gesture against the culture of individualism. The banishing of circulation space, and the design of rooms with windows that open not externally but internally towards the common areas, represents a radical proposal of respectful co-existence. Delicate paper models all around his office tell stories about his current projects; the Vitória Museum; laboratories for Vale do Rio Doce in Belem do Pani; the Vigo University building in Spain; and the Carriage Museum in Lisbon. The architect seems genuinely unconcerned about the current global economic difficulties. ‘How can Europe talk about crisis after having overcome two world wars and having rebuilt entire countries from scratch? We should allow capitalism to be discussed as well as reinvented,’ he says. Excerpt from an interview with Paolo Mendes da Rocha in 2010, by Isabel Martinez Abascal.

Villa Tugendhat, Czech Republic

‘They say that Prague is a baroque city, and Brno is a modernist one,’ says Czech architect Iveta Černá. Indeed the evidence is everywhere in the Moravian capital. In the first decades of the 20th century, culture, commerce and industry were in harmony in the city. This helped create its remarkable collection of early modernist buildings, which includes work by local functionalists Bohuslav Fuchs and Ernst Wiesner. Without a doubt, though, the city’s star architectural attraction is the Mies van der Rohe-designed Villa Tugendhat, which has renovated by a team directed by Černá. Sat on a slope offering sweeping city views, the villa is the epitome of modernity, a composition of low white volumes with a modest street façade featuring narrow openings and discreet milk glass. The three-level structure hosts a swathe of bedrooms at street level, with the main living areas and lush indoor garden above. The airy open-plan interior features an iconic strip-glass façade that overlooks a leafy, landscaped back garden.

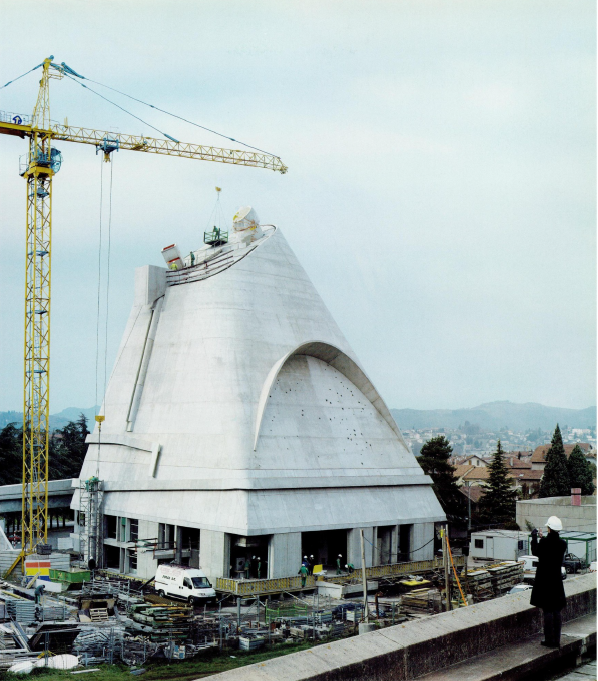

Church at Firminy, France

Le Corbusier's built legacy was extensive, yet his archive of unfulfilled schemes was even more so. One town that reaped more than its fair share of his genius was Firminy, in France's Loire Valley. In 1953, a determined post-war mayor decided that Firminy, a former mining town, was the perfect blank canvas for Le Corbusier's dreams of a vertical garden city: enter Firminy-Vert. The new town has three complete Le Corbusier works, but plans for a new church foundered as subsequent mayors weren't quite so keen on the brutalist style, and work slowly petered out, leaving an unfinished concrete shell. But thanks to former Le Corbusier apprentice, José Oubrerie, the builders returned to the site and the church was completed in 2006. Which is especially exciting because St-Pierre – a geometric composition dominated by a huge concrete cone punctured with slots that will allow light to cascade down into the nave – is only the third religious structure in Le Corbusier's oeuvre. The full version of this article was originally published in the February 2006 issue of Wallpaper*

Umbrella House, USA

When it comes to Sarasota modernism, it all began when progressive and well-travelled developer Philip Hiss had a vision for creating a wealthy winter enclave with a community vision for modern living. He commissioned up-and-coming architect Paul Rudolph (who had studied under Walter Gropius at Harvard and set up a local partnership with local architect Ralph Twitchell), to build forward-thinking structures for his land, resulting in, amongst others, the Umbrella House, a billboard for his new neighbourhood, Lido Shores. This two-level house was built as a marketing suite for Hiss’ Lido Shores neighbourhood, right next to his studio and on the highway as a billboard to modern living, designed by Rudolph. The structure is a steel grid with jalousie windows, and a huge 10ft shading canopy frames the pool and protects the windows from the sun. The canopy or ‘umbrella’ was originally made of old-growth cypress wood and tomato stakes, then replaced in 2015 with aluminium and steel wire X-bracing to meet hurricane-proof building codes that protect structures from 160mph winds. The ripe ground for building here drew other Sarasota School members Gene Leedy, Victor Lundy, Edward ‘Tim’ Seibert and ‘youngest member of the Sarasota School’ Carl Abbott, an ally of Architecture Sarasota who participated at MOD Weekend, amongst others.

Hamptons modernism, USA

Wesley Moon’s Xanadune Residence

The series of hamlets and seaside communities that form New York’s Hamptons region in eastern Long Island is no stranger to hidden gems, but probably most elusive of all is the plethora of modernist architecture homes that lurk in plain sight. Possibly thanks to furiously private owners, or because the properties have simply been forgotten, these historic houses are difficult to find, especially without a governing body in place to help preserve them. The newly established organisation, Hamptons 20 Century Modern, is committed to changing that. Founded by interior designer Timothy Godbold in early 2020 with a mission to raise awareness and recognition for preserving these modernist gems, the organisation is dedicated to preventing historically relevant homes from being lost to real estate development.

House in the Dune, USA

A modernist home designed by iconic American midcentury architect Charles Gwathmey, originally known as the Haupt Residence, has been given a new lease of life with a restoration and refresh by New York studio Worrell Yeung. The house, built in the 1970s in Amagansett, New York, cuts a distinctly modernist figure, sat among sand dunes and looking out towards the ocean – a positioning that lends it its name, House in the Dunes. Partially clad in grey cedar siding, which is matched by white walls and swathes of glazing, the house is a composition of opaque volumes and voids. These create windows, terraces, rooms and double-height living spaces indoors, in a design that feels at once dramatic and comfortably domestic.

Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, USA

Born in Osaka in 1941, Tadao Ando is well-known as self-taught, travelling the world to understand architecture across cultures as part of this learning. He set up his practice Tadao Ando and Associates in 1969. Since then, he has completed over 300 projects across his 50-year career, picking up the Pritzker prize in 1995. His back catalogue spans from his first house project in 1976, the Azuma House in Sumiyoshi, to the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth (2002), projects on Naoshima island that commenced in 1988, the Church of Light in Ibaraki, Osaka (1989), and La Bourse de Commerce in Paris, which opened in 2021.

Oceanus House by Pierre De Angelis and Donald Luckenbill

Oceanus House is a sun-drenched Los Angeles home revived through a design by the architecture studio of Pierre De Angelis, Good Project Company. Originally created in the 1990s by Donald Luckenbill (repurposing a significantly smaller 1975 structure on site), who worked in the office of Paul Rudolph for many years, the home features modernist architecture influences and minimalist architecture lines, which have been reimagined for the 21st century by De Angelis and his team. Oceanus House commands striking views of Los Angeles from the elevated Mount Olympus neighbourhood. As a result, the home is orientated towards the long vistas featuring large terraces and a swimming pool with lounge area that overlook the LA cityscape below. The refreshed home not only spans a striking 7,466 sq ft and four bedrooms, but also has an additional, fully independent (with its own kitchen and living space) pool house that adds 1,500 sq ft to the whole.

House PLR by André Becker of ABPA and Roberto Aflalo

House PLR is an intriguing synthesis of 1970s classic Brazilian modernism and contemporary work, set within a short distance from São Paulo’s Alfredo Volpi Park. André Becker of ABPA was commissioned to renovate an existing house, originally designed by the architect Roberto Aflalo (1926-1992) for his own family back in the 1970s. ‘The house is a very special project to me,’ says Becker, ‘as an important part of my education was the time worked at Aflalo/Gasperini Architects, the firm set up by Plínio Croce, Roberto Aflalo and Gian Carlo Gasperini in 1962.’ By the time Becker arrived, he worked under surviving partner Gasperini and Aflalo’s son, Roberto Aflalo Filho, and Felipe Aflalo Hermann. The commission sent him back to his former workplace to research the project. ‘I had access to all the original drawings to develop the renovation,’ he explains. ‘I was even able to hear some of Roberto Aflalo Filho's feedback about the experience of living in the house.’ The renovation went far beyond upgrading the fabric of the 1970s concrete structure. The new owner also bought the adjoining lots in order to balance out the main house with a new pavilion on one side and a rewilded forest area on the other.

A Trellick tower apartment by Buchholzberlin and interior designer Peter Heimer

A Trellick tower apartment has been respectfully refreshed to 21st-century standards by a team consisting of Berlin architecture studio Buchholzberlin and interior designer Peter Heimer. The piece of modernist architecture history was famously designed by architect Ernő Goldfinger and built between 1968 and 1972; it remains an exemplar of post-war modern architecture in London. The 86 sq m private apartment, which sits nestled on the 21st floor, was transformed to the needs of the two residents – the client and his partner – using brutalist architecture references from the structure's past blended with contemporary styles and needs. While respecting the Trellick tower apartment's original layout, the design team reimagined the spatial arrangement within the unit. The apartment is bathed with sunlight on three sides, so the architects worked to make the most of this orientation by uniting spaces and moving functions around.

Tadao Ando’s ‘Space of Light’

‘Space of Light’ by Tadao Ando is the second meditation pavilion opening at Museum SAN in Wonju, South Korea. Launching today (18 July 2023), this is the newest addition to the Japanese architecture master’s contemplative series, embodying his signature style expressed by concrete, light and integration with nature. Intense sunlight cuts through the square concrete structure, as two narrow slits on the roof intersect and solemnly light up the four walls of the cold, dark void. Although not conceived as a piece of religious architecture, the space invites visitors to an almost sacred moment of contemplation and self-reflection. At a glance, the pavilion might remind guests – at least those who follow Ando’s work – of his Church of Light in Osaka, Japan. The placement of the cross-shaped opening is the key difference between the two structures. The Church of Light has one at eye level on the main façade, and it is covered in glass. In the Space of Light, a similar opening is located in the ceiling and is open, with no glass to stop the elements from entering the space. 'In the Space of Light, the light falls in directly from the sky, just like the Pantheon in Rome,' says Ando. 'I believe this has a significant impact. When you look at light, there’s a feeling that touches the heart.'

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture Editor at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018) and Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020).

-

Gallery Fumi makes LA debut with works from Max Lamb, Jeremy Anderson and more

Gallery Fumi makes LA debut with works from Max Lamb, Jeremy Anderson and moreFumi LA is the London design gallery’s takeover of Sized Studio, marking its first major US show (until 9 March 2024)

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Brazil’s Casa Subtração contrasts dramatic concrete brutalism with openness

Brazil’s Casa Subtração contrasts dramatic concrete brutalism with opennessCasa Subtração by FGMF is defined by brutalist concrete and sharp angles that contrast with the green Brazilian landscape

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Level up at the The Residence, Claridge’s new André Fu-designed penthouse

Level up at the The Residence, Claridge’s new André Fu-designed penthouseClaridge’s The Residence is a new purpose-built two-tier glasshouse overlooking London’s skyline

By Lauren Ho Published

-

Is this the shape of wellness architecture to come?

Is this the shape of wellness architecture to come?Explore the future of wellness architecture through trends and case studies – from a Finnish sauna restaurant to UK cabins and a calming Canadian vet clinic

By Emma O'Kelly Published

-

Restored former US embassy in Oslo brings Eero Saarinen’s vision into the 21st century

Restored former US embassy in Oslo brings Eero Saarinen’s vision into the 21st centuryThe former US embassy in Oslo by Finnish American modernist Eero Saarinen has been restored to its 20th-century glory and transformed for contemporary mixed use

By Giovanna Dunmall Published

-

Discover Dyde House, a lesser known Arthur Erickson gem

Discover Dyde House, a lesser known Arthur Erickson gemDyde House by modernist architect Arthur Erickson is celebrated in a new film, premiered in Canada

By Hadani Ditmars Published

-

Georgie Wolton’s No. 34 Belsize Lane in Camden gets Grade II listing

Georgie Wolton’s No. 34 Belsize Lane in Camden gets Grade II listingNo. 34 Belsize Lane in Camden, London, by Georgie Wolton, is recognised as a modernist gem

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Minimalist architecture: homes that inspire calm

Minimalist architecture: homes that inspire calmThese examples of minimalist architecture place life in the foreground – clutter is demoted; joy promoted

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

The finest brutalist architecture in London and beyond

The finest brutalist architecture in London and beyondFor some of the world's finest brutalist architecture in London and beyond, scroll below. Can’t get enough of brutalism? Neither can we.

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

The iconic British house: key examples explored

The iconic British house: key examples exploredNew book ‘The Iconic British House’ by Dominic Bradbury explores the country’s best residential examples since 1900

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Loyle Carner’s Reading Festival 2023 stage presents spatial storytelling at its finest

Loyle Carner’s Reading Festival 2023 stage presents spatial storytelling at its finestWe talk to Loyle Carner and The Unlimited Dreams Company (UDC) about the musical artist’s stage set design for Reading Festival 2023

By Teshome Douglas-Campbell Published