The finest brutalist architecture in London and beyond

For some of the world's finest brutalist architecture in London and beyond, scroll below. Can’t get enough of brutalism? Neither can we.

Can’t get enough of brutalist architecture? Neither can we. In London, neglected brutalist behemoths are being rebooted and given new life. The wave of savvy renovations is being led by a flock of eagle-eyed developers who wish to save – and capitalise on – these concrete urban structures' dramatic shapes. This is not just a London-focused trend as more brutalist architecture around the world is being given a new lease of life. In London alone we counted contemporary renovations of Centre Point and the Economist Building as part of the movement.

Read this report of new developments at London’s Balfron Tower or visit Brussels where a brutal behemoth is being converted into a co-working space, while in the States a Marcel Breuer buidling in Connecticut is being reimagined as a hotel. Or scroll below, for some of the world's finest brutalist architecture in London and beyond.

Brutalist architecture in London

Centre Point, 1963-1966, by Richard Seifert & Partners

When completed in 1966, Centre Point represented a beacon of optimism within its original context of a run-down, post-war London, standing out for its avant-garde architecture and engineering. However, it remained underused for years until, in 2010, it was acquired by developer Almacantar, which enlisted Conran and Partners to bring the building into the 21st century. Now the design includes modern apartments, a lavish penthouse and a series of amenity spaces, including a pool and a private lounge/club house area with screening rooms and treatment rooms for residents and their guests.

Thamesmead, 1968

Housing at Thamesmead, Greenwich, London: view across the estate from an access deck, 1970s. © the artist / RIBA Collections

‘Thamesmead’. Semantically, the word sounds like a riverside Shakespearean ale house. But, in the public imagination, it conjures images of a 1970s, crime-ridden neighbourhood, and the droogish backdrop to Stanley Kubrick’s 1971 dystopian drama Clockwork Orange. Initially hailed as a futuristic ‘town for the 21st century’, construction of the London City Council-commissioned Thamesmead began in 1968. Despite early promise, it quickly gained a reputation for no-go areas and poor transport links. Recently, after a complicated history, punctuated by well-documented attempts to renew and rethink the area, Thamesmead has been undergoing an extensive regeneration project by Britain’s oldest housing association Peabody, which promises around 20,000 new homes, and improved community facilities. Additional writing: Elly Parsons

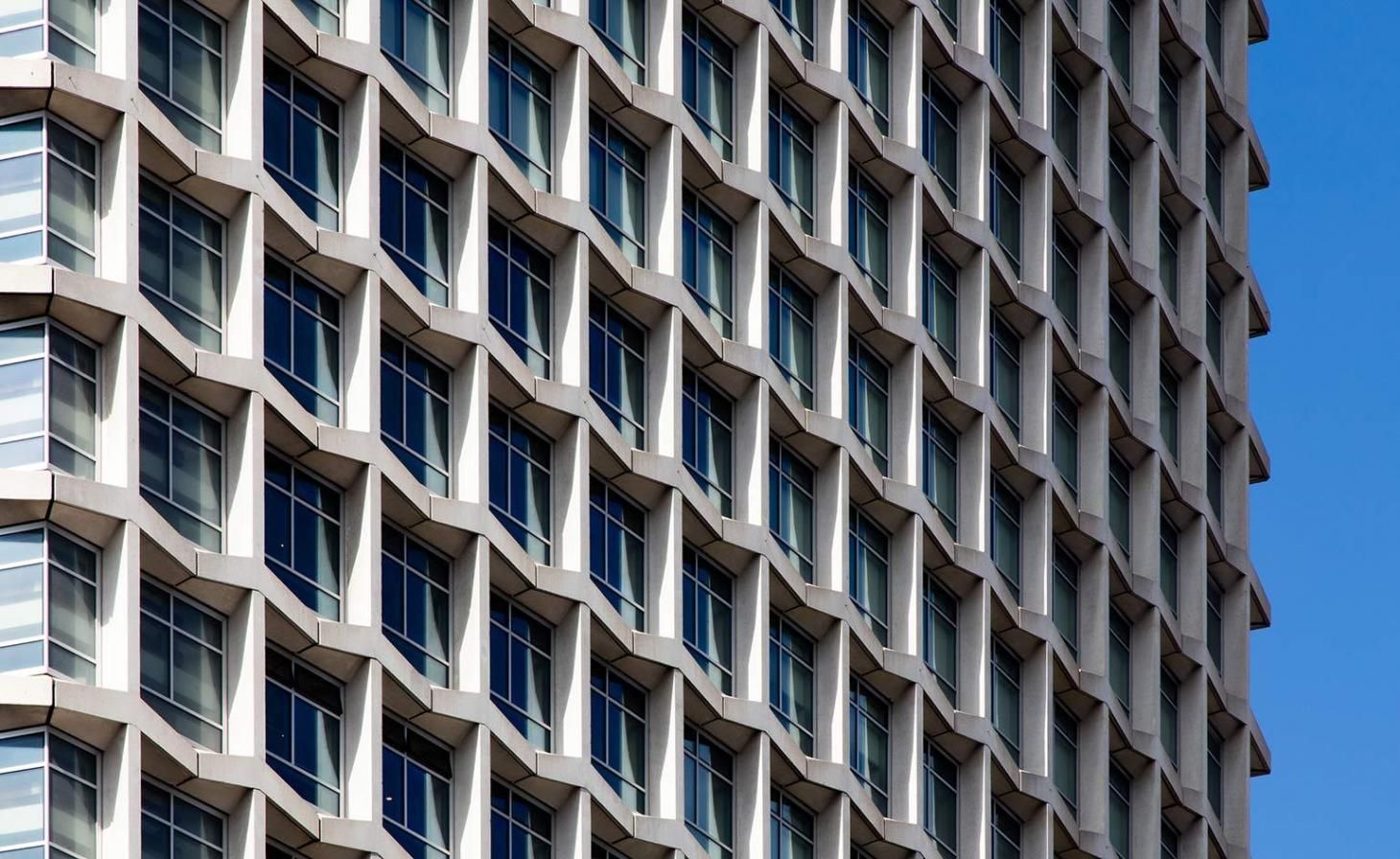

123 Victoria Street, 1970s, by Elsom, Pack & Roberts

Using Kvadrat curtaining, furniture from brands such as Vitra, Hem, Muuto and a specially-designed staircase, SODA Studio has conjured up classy offices in a brutalist block. The 40,000 sq ft workspace in London’s Victoria goes by the name of MYO, and is property firm Landsec’s first foray into flexible office space. SODA – the architects behind Soho’s new Boulevard Theatre – has converted the second and third floors of 123 Victoria Street, a 1970s building by Elsom, Pack & Roberts, which was refurbished eight years ago by Aukett Fitzroy Robinson. Inside, SODA took its cue from the blocky glazed exterior. ‘We didn’t want to fight against the building,’ says director Russell Potter. ‘Our driving principle was to create a rigorous grid with walls and partitions,’ which, he adds, they treated as ‘a kit of parts.’ These partitions add to the workspace’s flexible credentials. Additional writing: Clare Dowdy

Brixton Recreation Centre, 1974-1985, by George Finch

The now listed Brixton Recreation Centre, designed by architect George Finch and completed in the mid 1980s is one of the new additions of remarkable brutalist architecture included in the refreshed Brutalist London Map (Second Edition) by Henrietta Billings and with photography by Simon Phipps, published by Blue Crow Media. The map aims to highlight London's rich legacy in brutalist architecture in order to celebrate and help save many buildings from demolition. 'In 2022, seven years on from the first edition of the map, the environmental impact of demolishing these buildings and their vast stores of embodied carbon is alarmingly clear. From a sustainability, as well as a heritage perspective, we cannot afford to lose any more of them,' says the author. More buildings that made their way into the map for the first time are the National Archives at Kew; Blackheath Meeting House; the Royal College of Art’s Darwin Building; and the Camden Town Hall Annexe, recently converted into the Standard Hotel.

Economist Building, 1959-1964, by Alison and Peter Smithson

‘You’d originally sit with a typewriter on the windowsill, then swing round and write longhand at your desk,’ says Deborah Saunt, explaining the Smithsons’ tailor-made office space in the Economist Building for The Economist magazine. Saunt’s practice, DSDHA, won the competition to refurbish this London icon, a building that took the raw pragmatism of brutalism in another, very different direction. The best-known shots of the structure – three ‘roach bed’ Portland stone-clad towers around a central plaza – were taken by a young Michael Carapetian, a friend of the Smithsons who brought a cinematic, reportage-like quality to his images. The AA-trained architect recalls that he ‘wanted a day that was slightly misty and wet. It was the first time a new building had been photographed in the rain.’ The imagery cast has a moody, atmospheric light. ‘It wasn’t seen as shocking, but the building was respected for its ability to blend in with the rest of the street,’ he recalls. ‘The idea was to elevate the plaza above the rest of the street – a sort of utopian idea.’ Saunt says the practice envisaged the structure as a blueprint for a new form of urbanism, linked by walkways and quasi-public spaces. Her studio’s modest but comprehensive refurbishment strips away interiors that themselves were wholesale replacements of Smithsons’ careful original detailing. ‘We’ve made it a lot more harmonious, but have embraced their vision of architecture as a framework,’ she says. The revitalised building will see one of London’s most elegant public spaces brought back to life.

National Theatre, 1976, by Denys Lasdun

The National Theatre courted controversy from the outset, with the UK's favourite architectural scourge, Prince Charles, casually dismissing the capital's new cultural flagship as a ‘nuclear power station’. Sir Denys Lasdun's rigorously composed concrete statement still looks at fresh as ever, thanks to an £80m refurb by Haworth Tompkins in 2015, not to mention the quality of the original design. With generous terraces that step down to the Thames and a monumental assemblage of interior volumes, spaces and stages, it remains one of London's contemporary classics. The city is also home to Lasdun's other masterpiece, the 1964 Royal College of Physicians, a Brutalist stage set of concrete and stone, rising up amongst the genteel stucco terraces of Regents Park. Lasdun's Theatre refined the aesthetic that had already been established by the adjacent Hayward Gallery and the Queen Elizabeth Hall. These buildings still represent a substantial chunk of London's cultural infrastructure and were built between 1960 and 1968 on the site of the Festival of Britain, alongside the remodelled Royal Festival Hall. Designed by a team of architects employed by the Greater London Council – including key members of the iconoclastic Archigram studio – this group of buildings represents concrete at its most diverse and distracting, a collage of textures and forms that rises up beside the river in a thrilling urban jumble. Much loved, forever threatened, but an integral part of the London experience

Alexandra Road Estate, 1968-1978, by Neave Brown

Social housing at its most optimistic, aesthetically sophisticated and single-minded best, the Alexandra Road Estate snakes alongside a railway line in Camden, containing over 500 homes in a variety of configurations. Created by the late Neave Brown – then working in Camden Council's Architecture Department – it went wildly over-budget and later found infamy as a location for dystopian films and television. Yet despite the controversy it continues to be a desirable place to live, with its shuttered concrete flanks rising steeply above a pedestrianised central street.

One Kemble Street, 1968, by George Marsh

This cylinder and box office block is a typical piece of Sixties grandstanding, almost entirely blasé about its immediate surroundings. These days it finds itself an integral part of the eclectic cityscape. Designed by George Marsh, one of the partners in Colonel Richard Seifert's massive commercial architecture outfit, the circular building showcased Seifert's trademark angular modular façade and muscular supporting columns. It was also the HQ to the UK's Civil Aviation Authority for many years. Currently, the central London structure - also known as Space House - is being given a new lease of life by developers Seaforth Land and architects Squire and Partners, who are on site with a transformation of the iconic shell into modern office and retail spaces.

Brunswick Centre, 1972, by Patrick Hodgkinson

Patrick Hodgkinson's original vision for Bloomsbury consisted of a vast trench of concrete dwellings and lecture halls, stomping across the remnants of Georgian London with Brutalist glee. The only chunk to be finished, the Brunswick Centre, is perhaps London's sole megastructure, a concrete valley of houses arranged above a shopping parade and cinema. It took three decades before a programme of refurbishment and upgrade works covered the raw concrete in the paint Hodgkinson originally specified. Now a highly desirable and light-filled place to live, it offers an insight into the grandiose schemes of decades past.

The Barbican Estate, 1965-1976, by Chamberlain, Powell and Bon

For many Londoners the Barbican defines contemporary Brutalism. Yet behind the fortress-like construction of this 35-acre city centre site is a veritable oasis of greenery, culture, water and calm, all wrapped up in some of the most abrasive concrete finishes ever seen. The Barbican almost took as long to build as a city, with initial plans drawn up in the 50s and the final concrete slotted into place in the arts centre, which opened in 1982. The firm of Chamberlain, Powell and Bon oversaw this expansive piece of urbanism, which continues to define the highest standards of concrete design.

Keeling House, 1957, by Denys Lasdun

An earlier outing by Denys Lasdun, Keeling House in East London was intended to form a 'street in the sky', replacing the low-rise back-to-back houses that had succumbed to war damage and old age. The cluster block form was carefully designed, with interlocking, overlooking apartments somehow combining both community and privacy, but it was rather less meticulously built. By the early 90s the block had fallen into disrepair; a pioneering refurbishment by Munkenbeck and Marshall gave it a new lease of life, adding penthouses on top and even securing Lasdun's blessing in the process.

Trellick Tower, 1966-1972, by Ernö Goldfinger

The Trellick Tower is the archetypal symbol of brutalism in West London, a bold cliff of shuttered concrete that overlooks the city's western reaches. Despite a rocky start, the Trellick subsequently ascended to the status of cultural icon, adorning everything from t-shirts to coffee cups. Ernö Goldfinger's generous design initially suffered from poor maintenance but today the building's generous apartments are highly sought after, combining space, light and views, with services pushed to one side and contained in a slim adjoining tower.

78 South Hill Park by Brian Housden

Hampstead Heath’s 78 South Hill Park doesn’t look like a house born of embarrassment, but that is exactly what it is. In the 1950s, architect Brian Housden visited Dutch De Stijl master Gerrit Rietveld (who played roughly the role in architecture that Mondrian played in painting) and, when they parted, Rietveld told Housden he’d love to see the plans of the Hampstead house he was working on. Housden said he was mortified, ashamed of the timid designs he had drawn and decided to start over. Rietveld never saw the drawings, but the result is extraordinary – a brutalist house on the edge of Hampstead Heath that is one of London’s most surprising and inventive post-war dwellings. The 1924 Rietveld Schröder House, which so inspired Housden, is always photographed as a freestanding, almost autonomous building, but, in fact, bookends a dull brick Utrecht terrace. Similarly, Housden’s house squats between a pair of more conventional modernist blocks (including one by Howell, Killick, Partridge & Amis, architects of London’s Young Vic theatre), its muscular concrete frame seeming to push them apart, to defy them to crush it. Additional writing: Edwin Heathcote

Barbican sunken bars by Kam Bava

The much loved Barbican Estate in London comprises many parts and elements – from its famed performing arts centre, a key cultural hub in the City of London and beyond and the largest of its kind in Europe, to its iconic residences, outdoor spaces and brutalist architecture environment. Its scale means that there are many smaller areas, however, which often remain lesser-known, yet are no less important to the Barbican experience. Part of the Grade II-listed Barbican Centre Theatre, the Barbican sunken bars are two hospitality corners of the seminal modernist development, constructed between 1965 and 1971 and located under the steps of the theatre. The spaces were in need of a refresh, so London architect Kam Bava was asked to lead a careful restoration and interior redesign to breathe new life to the complex's much-loved leisure offering.

The bars’ facelift was not just about aesthetic fixes and a superficial polish. The architect ensured a technical upgrade was incorporated as well, because, after years of intensive use, the listed fabric was in dire need of an update. Seeking to maintain the interior's original character, as well as emphasise reuse and recycling as an approach, Bava cleverly redeployed elements found within the Barbican campus. ‘The steel bar structure is made from the handrails on the [Barbican] centre, and the ceiling comes from the art gallery. The handling of these pieces together with the use of mirrors creates a very different scale of experience, using very familiar design cues,' he explains. Read more

South London house by Whittaker Parsons

This brutalist treasure in south London squeezes a surprising amount of space onto an unpromising spot, enhancing the streetscape. The addition, next to a terraced house, features a tough, hard-wearing exterior that brings a little brutalist architecture glamour to its neighbourhood. Whittaker Parsons’ Corner Fold House was designed for a downsizing couple, who swapped a conventional Victorian terrace for a faceted modern house that makes the most of its awkward site, tucked in between an immovable electricity sub-station and the clients’ former family home. The process was remarkably smooth, according to the clients, who were able to transform a garden plot at the side of their house into a completely separate dwelling, digging down to create a new basement and even finding enough space for a small rear terrace. Describing it as ‘the experience of a lifetime’, the clients are especially impressed by Whittaker Parsons’ ability to maximise the amount of available space.

Brutalist architecture globally

Habitat 67, Montreal, by Moshe Safdie

As Portland’s cement industry bloomed at the turn of the 1900s and architects became increasingly tired of conventional materials, Montreal became something of a playground for concrete experimentation. From Moshe Safdie’s Habitat 67 – the instantly recognisable model community on the Marc-Drouin Quay – to Roger Taillibert’s monolithic Olympic Stadium, constructs of all shapes and sizes are brought into the fold.

CBR HQ, Brussels, Belgium by Constantin Brodzki

Constantin Brodzki is less than enthusiastic, to say the least, whenever he hears of one of his buildings being renovated. At 93 years old, the Belgian architect is still very much engaged with the architecture world, and he’s eager to point out the ways in which he would like his modernist legacy to be preserved. ‘I have experienced catastrophes before, so I’m suspicious,’ Brodzki admits, taking out plans and photos to show how some firms have botched his former projects. One of his designs, the former HQ of the cement company CBR in Brussels, is currently being converted into a new outpost for Antwerp co-working concept Fosbury & Sons. Close to the Sonian Forest, it’s just ten minutes from the high-end Avenue Louise. For Fosbury & Sons’ founders Stijn Geeraets and Maarten Van Gool, the initial impetus to take on the modernist office building, with its characteristic façade of curved concrete modules, was all about the immediate visual impact. But as they started to explore the building, the full package captivated them. Additional writing: Siska Lyseens

Zvonarka Central in Brno, Czech Republic

Brno’s Zvonarka Central Bus Terminal has been a key Brutalist architecture landmark in the city since it first opened in 1988 - and is among the country’s most notable remaining examples of the genre. But years of intense use and high maintenance costs had resulted in a tired, decaying building in dire need of a refresh. Now, the Brutalist bus terminal has been given a new lease of life courtesy of architects CHYBIK + KRISTOF, who in 2011 embarked on a self-initiated journey to restore the famous building to its former glory. The design team worked with the station’s private owners and raised awareness through social media to instigate a discussion about the station’s future, securing the necessary funding for the redesign works in 2015. ‘Demolitions are a global issue,’ explains co-founding architect Michal Kristof. ‘Our role as architects is to engage in these conversations and demonstrate that we no longer operate from a blank page. We need to consider and also work from existing architecture – and gradually shift the conversation from creation to transformation. Read more

Van Wassenhove House, Belgium by Juliaan Lampens

Those, like us, who have a soft spot for crude concrete architecture, will love the work of Juliaan Lampens (1926-2019). The powerful concrete roughness of the Belgian architect’s volumes is inescapable when you walk past two of his best known buildings, both near Ghent: the Chapel of Our Blessed Lady of Kerselare, in the village of Edelare, and the Van Wassenhove house in Sint-Martens-Latem. However, digging a little deeper into Lampens’ life and work, it quickly becomes apparent that there is more to his architecture than brutalism by numbers. Belgian curator Angelique Campens has been studying Lampens’ work since her university years and knew him well. The architect had a reputation for being reserved, keeping his business to himself to the point of avoiding contact with colleagues. He didn’t even travel much, reveals Campens. ‘But he had a lot of books. He admired Oscar Niemeyer and was influenced by Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe.’ He may seem to have lacked the desire for architectural pilgrimage, but Lampens practised non-stop from his base in Eke, East Flanders, from 1950 until his last work was built in 2002 – creating a legacy of about 50, mostly residential, projects, including the chapel and Eke library. Lampens was born in 1926 in De Pinte and grew up in nearby Eke, the son of a cabinetmaker. After working as a technical draughtsman, he studied architecture in Ghent and set up his own firm straight after graduation, kick-starting it with commissions from his father’s middle-class clientele. While following a more conventional design style at first, he nurtured an interest in modernism. ’His visit to the 1958 World’s Fair in Brussels was a turning point for him,’ Campens explains. ’Shortly after that, his designs changed drastically. He thought that Le Corbusier was too sculptural, and Mies too structured, but he wanted to combine the two. Read More

Armstrong Rubber Building, aka the Pirelli Tire Building in the USA by Marcel Breuer

Iconic examples of landmark architecture might not typically be found along major highways, but this is exactly where this brutalist architecture masterpiece, designed by Marcel Breuer, has cut a recognisable figure since it was completed in 1970. Located in New Haven, Connecticut, just off of the Interstate 95, the main north-south highway running along the east coast of the United States, the concrete behemoth was first created for the Armstrong Rubber Company, a tyre manufacturer – making its location apt. Originally designed to house the company’s administrative offices as well as a research and development space, Breuer’s sculptural concrete building is interrupted by a void of negative space. This was intended to help buffer and reduce sound for the offices above from the research labs below. It was finished with a façade created from pre-cast concrete panels that offer shade and protection from glare, while creating a dynamic visual tension. The building, which was bought by Pirelli in 1988 as its North American headquarters, was added to Connecticut’s State Register of Historic Places in 2000. Additional writing: Pei-Ru Keh. Read More

Flying Saucer, Sharjah

The ‘Flying Saucer’ is one of Sharjah’s key Brutalist architecture landmarks. The round, striking building, which was originally constructed in the 1970s and opened in 1978 as a mixed use structure, was acquired by the Sharjah Art Foundation (SAF) in 2012. Then in a state of disrepair, it has now been given a new lease of life through a thorough renovation by the foundation and architect Mona El Mousfy of SpaceContinuum Design Studio. While the structure was originally conceived to house a one-stop-shop restaurant, newsstand, tobacconist, gift shop, patisserie and delicatessen, after the restoration and redesign, the Flying Saucer is reimagined as an art and community space with a café, library, courtyard and activity spaces. Read more

Boston City Hall, 1969, by Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles

Few buildings have been more controversial than those belonging to the brutalist genre; and Boston City Hall is no exception. When its concrete block volumes were unveiled on the 10 February 1969, the launch was underscored by as much fanfare as criticism. Yet, it has now become a much-loved landmark of contemporary architecture, recognised as one of the brutalist movement’s most significant expressions. And the striking building has just marked the 50th anniversary of its grand launch. Designed by Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles, the Boston City Hall was part of the area’s greater government complex redesign and was created following an international competition. The structure is dramatic, featuring cantilevered elements and a highly articulated concrete facade that is instantly recognisable. The Boston City Hall in Massachusetts, USA, by Kallmann, McKinnell & Knowles has recently celebrated the 50th anniversary from its opening. Concrete Architecture and the New Boston’ (Monacelli Press) Read More

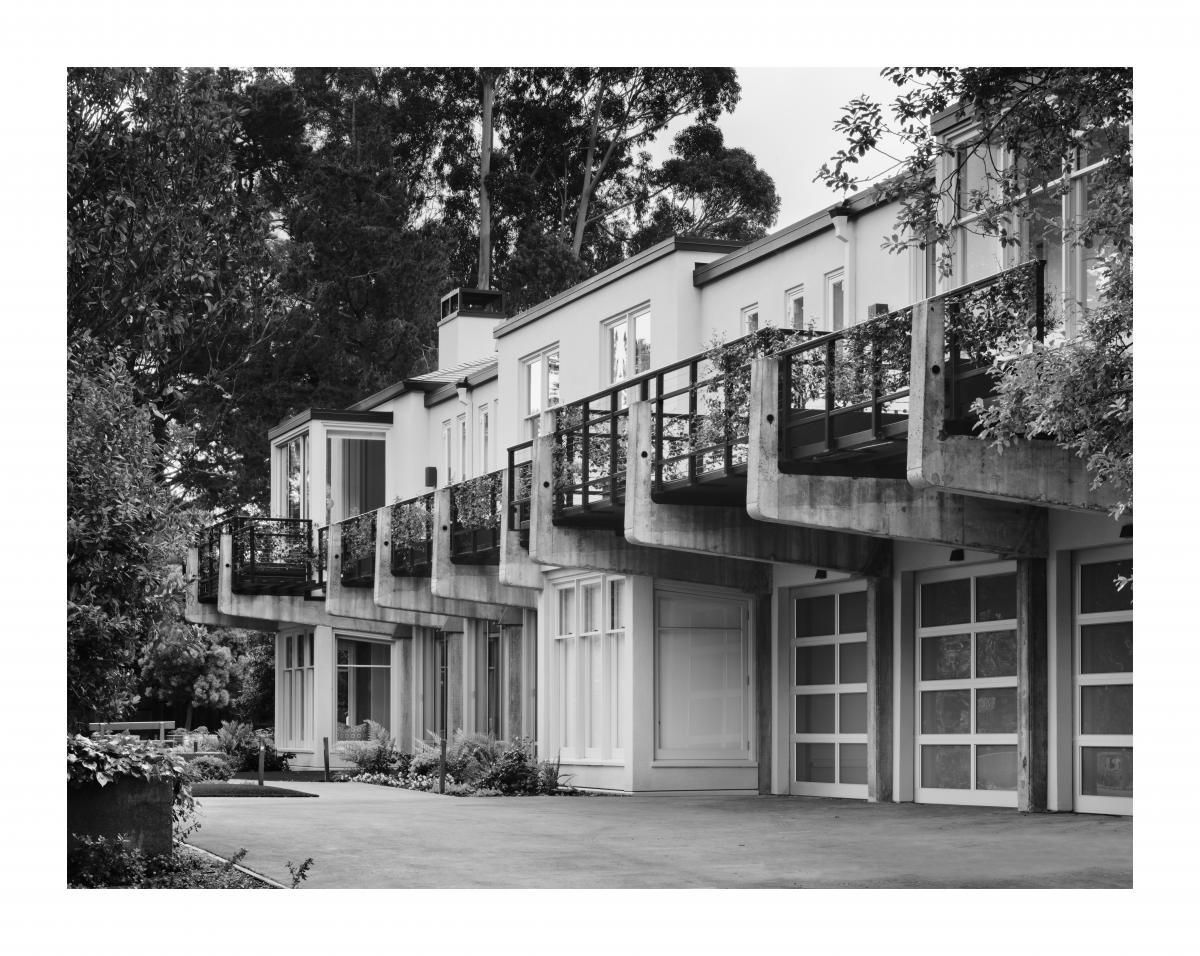

San Francisco home, early 1960s by architect Joseph Esherick

An early 1960s San Francisco residence by architect Joseph Esherick has been brought to the 21st century by Richard Beard Architects and The Wiseman Group. The team worked with the original midcentury home’s brutalist architecture, implementing contemporary interiors to accommodate the owners’ art collection and make the home suitable for a family of five. ‘[We wanted it to be] respectful of the heritage but looking to the future,’ says architect Richard Beard. With the home’s main brutalist space, the atrium living room, featuring exposed concrete and a high, skylight ceiling, Beard admits that making it feel ‘cozy’ was challenging. Yet the architecture team balanced preserving the building’s original character and architectural intention with making changes. ‘The character of the house is and was defined by a number of distinctive details and materials,’ explains Beard. ‘Those we preserved, and enhanced. It would have been a shame to turn the house into just another lovely suburban home. What was odd was the compartmentalised plan. At a time when open plans were becoming an innovative architectural approach to composition, this house was comparatively segmented. We carefully opened a few things up, to give a more expansive feeling through the home.’ Read More

Eduardo Leme House, 1969 by Paulo Mendes da Rocha

When art dealer Eduardo Leme was a boy in São Paulo, he used to look out with endless fascination at a striking modernist house two blocks away. It was the home of Brazilian architect Paulo Mendes da Rocha. When Leme saw a ‘For Sale’ sign outside another da Rocha concrete bunker-style house in the city, he decided to buy it. Known as Casa Millán, it had been built in 1969 for another art dealer, Fernando Millán, and was in serious need of a facelift. Leme called on da Rocha himself to fix it up and a friendship was formed – which resulted the architect building Leme the São Paulo art gallery he owns today. As for the updated residence, ‘the concrete gives the house a very informal feel’, says Leme. ‘It’s the sort of place where you feel at home in shorts and a T-shirt.’ The relaxed vibe is added to by the fact that the house overlooks a quiet local park teeming with monkeys and super-sized vegetation, and has a swimming pool in the garden. Additional writing: Emma O'Kelly Read More

Casa Mérida by Ludwig Godefroy

The first thing that stands out about Casa Mérida is its unashamed brutalism, defined by raw and omnipresent concrete, all hard edges and rough surfaces under the strong Mexican sun. The second is that most of the building seems to be open to the outdoors, with few fully enclosed spaces. The project’s defining feature, though, is that it is 80m long but just 8m wide. While this odd stretch would be considered unusual in most places, in Mérida, capital of the Mexican state of Yucatán, it’s fairly common, explains the house’s architect, French-born, Mexico City-based Ludwig Godefroy: ‘This type of lot is everywhere in the historic centre of Mérida and it has to do with inheritance, when people started to slice bi er plots into smaller ones, to distribute to different siblings.’ And while a big part of the city comprises grand colonial architecture, some urban chunks include more humble styles, such as old workers’ cottages. It was one such building that Godefroy came across, when he visited Mérida with his client, a high-flying professional from Mexico City. His family of three was in search of the perfect spot for a retreat, to hide away and use as a base to kite-surf nearby. The strange plot was a quirk Godefroy embraced immediately. ‘The house’s long and narrow site provided a new kind of challenge for me,’ he says. ‘It’s nothing like I’ve done before and by pushing yourself, something new and amazing can come up.’ Read more

Punchbowl Mosque by Candalepas Associates

Sydney’s Candalepas Associates has brought a slice of brutalism to the city’s Punchbowl suburb with an orthogonal new mosque. The concrete structure provides a new home for the Australian Islamic Mission, and its various educative and community facilities can host up to 300 worshippers at once. The mosque forms the first of a two-part project for the local Islamic community. The second stage of the plan will see the development of new community buildings that will orbit the place of worship, in turn bringing the local faith closer together. Candalepas Associates was resultantly driven to give the mosque a unique architectural vernacular, so to help it stand separate and distinct from its future sibling spaces. Additional writing: Luke Halls. Read More

Clifton cathedral (1969-73) by Ron Weeks of the Percy Thomas Partnership

Architecture buffs might recognise the brutalist cathedral in Clifton, Bristol by its distinctive, irregular, elongated hexagonal floorplan. What many don’t know however, is that the iconic building has been suffering from water leakages for years, due to its large, striking lead roof not being entirely watertight. Enter architecture and heritage experts Purcell, who have just unveiled their careful repair work to the building’s historical fabric, rendering the cathedral fully watertight for the first time ever. The structure, also known as Roman Catholic Cathedral Church of SS. Peter and Paul in Clifton, Bristol, was originally constructed between 1969-73 to a design by Ron Weeks of the Percy Thomas Partnership, and is a Grade II* listed monument. Due to the building’s sensitive and historical nature, Purcell worked closely with all relevant parties and the Lead Sheet Association to ensure the greatest care is taken when carrying out the repair works. The latter was heavily involved because the pitched roof required the majority of the works – some 86 tons of replacement lead. It was the largest lead roofing project in Britain at the time of its creation. Read more

Rozzol Melara in Trieste, built under the direction of Le Corbusier in the 1960s

Hefty monographs about concrete were everywhere in 2017. Once a marginalised and maligned genre, brutalism has burst back onto the design scene, cited as inspiration by a new generation seduced by the authenticity and heroic ambitions of this impressive architecture. Yet as well as being fetishised for its rough and ready qualities, there’s also a growing desire to preserve the best examples of concrete architecture in the face of widespread indifference and downright hostility. SOS Brutalism, a monumental survey of the more esoteric expressions of concrete architecture around the world, with a special focus on those that are threatened by alteration or demolition. This impressive book, which grew out of a collaboration between the Deutsches Architekturmuseum and Wüstenrot Foundation and was edited by Oliver Elser, Philip Kurz, Peter Cachola Schmal, is a treasure trove of unsung buildings and oddities, including works in Russia, the Middle East and Asia. Covering the period between 1950 and 1970, it uses new photography and archive imagery to rally for preservation and recognition, making it a must for lovers of architecture’s more far-flung fringes. Lovers of raw surfaces, bold forms and naked concrete are spoilt for choice. Additional writing: Jonathan Bell. Read More

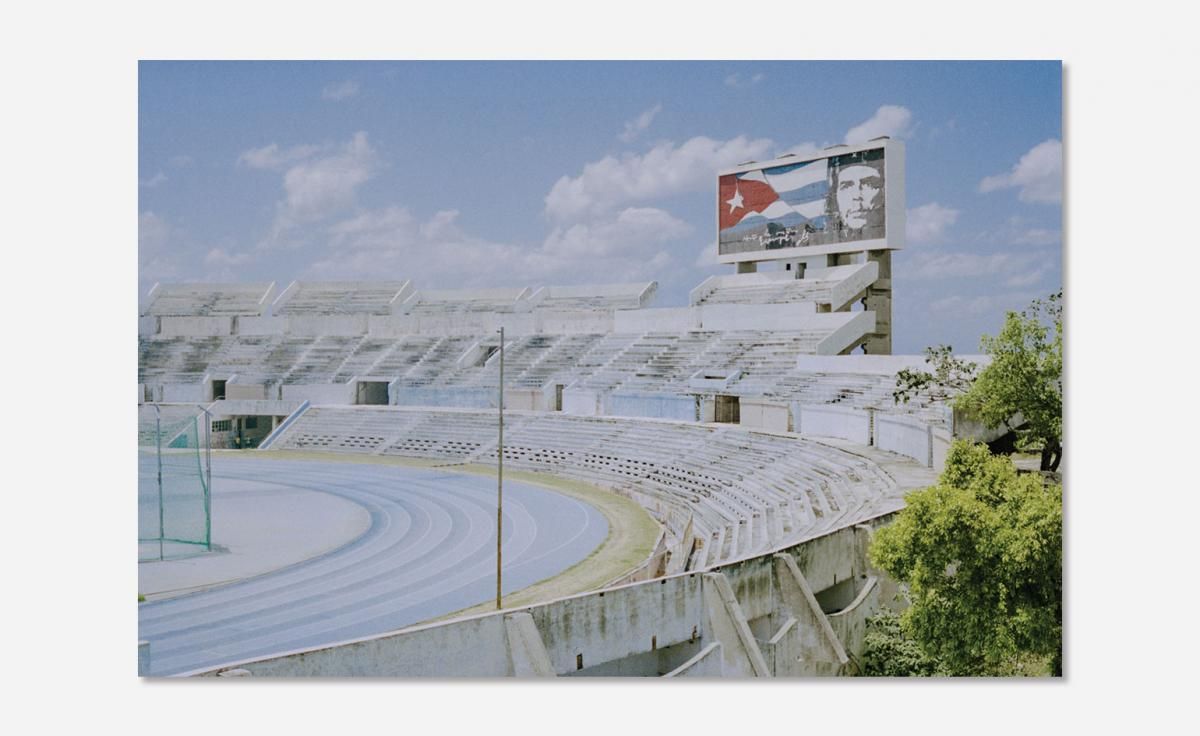

Various sites in Havana, Cuba

A few years ago, we tasked renowned New York-based photographer Daniel Shea to capture Cuban creativity, ahead of Chanel’s landmark Havana Cruise show. On the eve of Chanel’s landmark Havana Cruise 2016 show, we dispatched New York photographer Daniel Shea to shoot a portfolio of the Cuban creatives who are driving the country’s new cultural revolution. We asked him what his initial impressions were of Havana. He says: ‘Driving in from the airport, the first thing I noticed was the architecture, which felt unique to the place and its various competing histories, including colonialism. The combination of historical preservation, ruin and the sprinkling of new construction creates the Havana density, plus the beautiful colours and strong, hot sunlight bathing everything.' Additional writing: Katrina Israel. Read more

Yale Centre for British Art, USA, by Louis Khan

Louis Kahn’s masterful Yale Center for British Art re-opened its doors in 2016 after the completion of a $33 million, eight-year renovation led by New Haven-based Knight Architecture. The five-story 1974 building houses the largest collection of British art outside of the United Kingdom, donated in 1966 by Yale Alumnus Paul Mellon. Its intimate, naturally lit galleries are organised around two ethereal interior courtyards, floored in travertine and clad with grids of bared concrete, matte steel and white oak wall panels. Perhaps most famous for its monolithic anchor piece, a drum-like cylindrical grey cement staircase— the centre is an astonishing example of Kahn’s unparalleled gift for eliciting visceral emotion through pure volume, light, and materials. Much of the renovation, describes Knight Architecture principal George Knight, was ’an effort to defend the architecture in the face of legitimate issues.’ Additional writing: San Lubell. Read more

The home of Pedro Reyes and Carla Fernandez in Mexico City

This is a dwelling for the caveman of the future; the ruins of a civilization, now extinct, which was more advanced than the one we’re living in now,’ explains Mexican artist Pedro Reyes. He’s referring to the house he’s built with his wife, fashion designer Carla Fernández, in Coyoacán, in the south of Mexico City. Ancient Aztecs meet The Martian Chronicles in the form of hammered concrete walls, chunky furniture hewn from volcanic stone and an abundance of rich, overblown greenery. A ‘pyramid’ at one end is Carla’s studio, a yard behind it will be Pedro’s. It’s currently a ramshackle plot occupied by the team of artisans that is helping finish the house. The couple is in good company in Coyoacán. Fellow artists Damián Ortega and Gabriel Orozco are nearby, Frida Kahlo was born locally, and it’s where her pal, the exiled Leon Trotsky, was murdered in 1940. Those in Mexico’s creative circles joke that Carla and Pedro are the modern-day Frida and Diego (Rivera, Kahlo’s artist husband). Like their predecessors they are bon vivants – 600 guests came to their housewarming – and like their communist forebears, they are politically engaged. Additional writing: Emma O'Kelly. Read more

County Hall, Truro, FK Hicklin, 1963-66

Owen Hatherley – author of a new book on Britain’s modern buildings – is an architectural journalist with an agenda. Throughout a series of memoirs and travelogues spanning the UK and Europe, Hatherley has proved to be one of the most perceptive and insightful chroniclers of the modernist era. His urban perambulations are in the great tradition of some of the best writers on architecture and design, from Nikolaus Pevsner through to Ian Nairn, Jonathan Meades, and Reyner Banham. Like these critics and historians, Hatherley is adept at eking out some additional fact or stylistic note, while never being afraid of pronouncing an unpopular opinion. Among the buildings featured is Truro Town Hall, pictured here. Additional writing: Jonathan Bell Read More

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Municipal Stadium, Ahmedabad, India. 1959 – 1966

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Municipal Stadium, Ahmedabad, India. 1959 – 1966. Architect: Charles Correa (1930 – 2015). Engineer: Mahendra Raj (b. 1924). Exterior view

Emancipatory politics in the first decades after the end of colonial rule in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka are given a physical shape, thanks to the Museum of Modern Art’s latest exhibition, ‘The Project for Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia 1947 – 1985’, which opens this week. Comprising over 200 South Asian architecture works ranging from original sketches, drawings, and photographs to films and architectural models, the survey focuses on work by prominent leaders and institutions from the region, including the Indian icon Balkrishna V Doshi, currently the only South Asian winner of the Pritzker Prize in architecture; trailblazer Minnette de Silva, the first female licensed architect in Sri Lanka; and Yasmeen Lari, the first woman who qualified as an architect in Pakistan. The pictured, by Charles Correa is among the featured works. Additional writing: Pei-Ru Keh Read More

Casa Zicatela, Mexico

‘Emotional architecture,’ muses Emmanuel Picault, enveloped in a cloud of cigarette smoke at his flat in the trendy Roma district of Mexico City, ‘is one we cannot plan.’ He is referring to the term coined by the German-born Mexican artist Mathias Goéritz in 1953, which describes an architecture elevated to art for the purpose of inspiring emotion. Known primarily for their work on nightclubs and bars, French architectural duo Picault and Ludwig Godefroy, who are based in Mexico, have developed an intuitive and spiritually charged style that mixes modernist and pre-Hispanic influences. Picault is a well-known figure in the Mexican capital. With no formal training, he made a name for himself in the 2000s running Chic by Accident, a visionary antique gallery often credited with reviving interest in 20th-century Mexican design. He also worked on some acclaimed interiors projects, including the Revés bar in the upscale district of Polanco in 2007, which shot him to the forefront of the design scene. Godefroy moved to Mexico in 2007 to work as an architect at Tatiana Bilbao’s studio, after a stint at OMA in Rotterdam. ‘Ludwig brought a strong architecture background to the table, which I didn’t have,’ says Picault, who likes to describe himself as an ensemblier (literally one who ‘brings things together’). Although they originate from neighbouring towns in Normandy, the pair met at a jazz bar in Mexico City. Excited by the potential of their combined skills, they decided to team up in 2010. Additional writing: Benoit Loiseu Read More

University of East Anglia in Norwich (1962–68) by Denys Lasdun

Courtesy Museum im Bellpark

Our admiration for all things concrete is part of our DNA, so when we found out about fine art photographer Simon Phipps’ book on brutalist architecture, Finding Brutalism: A Photographic Survey of Post-War British Architecture, we were rubbing our hands together in glee; and when the book reached our offices, it did not disappoint. Filled with Phipps’ distinctive photographic compositions, this is a richly produced tome. The photographer spent more than 20 years, documenting brutalist architecture in Britain, creating a hefty archive of about 125 buildings. The book features some 200 takes of those, making for an impressive collection to reference and savour. Yet if you think that this is all about aesthetics, think again. Phipps, in effect, follows through his lens the rebuilding of Britain after World War II. His numerous photographs of Brutalist masterpieces not only appeal to the eye and refined tastes, but also ‘recognises the architects’ enormous contribution to the transformation of the political and social landscape of the country’ in the aftermath of the war, explain the publishers, Park Books. Included is the University of East Anglia in Norwich (1962–68) by Denys Lasdun, pictured here. Read more

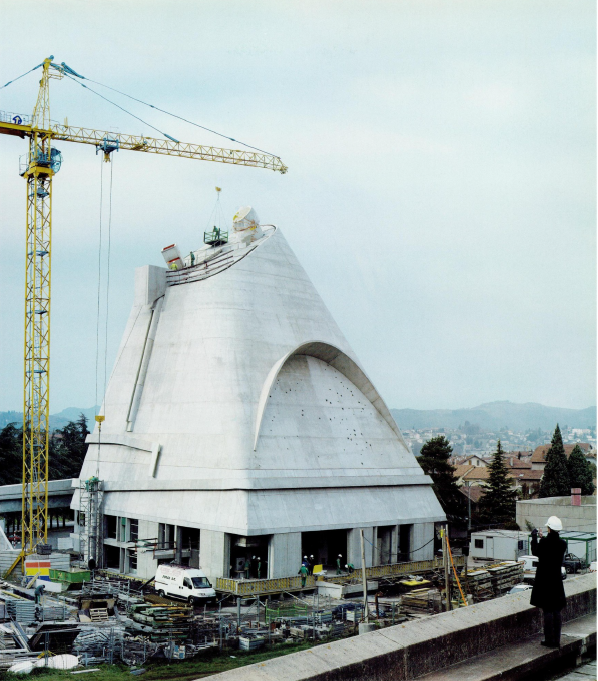

Pilgrimage Church, 1968, by Gottfried Böhm (1920-2021)

Architecture is one of those professions that can often become a family affair. Gottfried Böhm is not only the son of an architect, he is also the grandson, the husband and the father of architects. Since the early days of his career, more than 60 years ago, Böhm has been known for his original work, which, in 1986, earned him the Pritzker Prize. The Pilgrimage Church in Neviges, Germany, perfectly characterises his style – and is nothing like any church you could imagine. The Pilgrimage Church project began as a competition-winning entry in 1964, in response to the Catholic archdiocese of Koln’s call for a church in Neviges, a small town about half an hour outside the city. Böhm’s winning design ticked all the boxes, providing both the space and atmosphere for religious functions – it offers seating for 800 and standing room for 2,200 in a truly spectacular building – without any obvious recourse to traditional religious symbolism. The church was completed in May 1968 and instantly became a landmark in the town. Taking advantage of a row of pilgrims’ houses and the church’s position at the top of a slope, Böhm created a processional way leading up the hill, into the church’s open courtyard and inside, ending at the altar and the pilgrimage’s religious climax. Read more

Teatro Politecnico, 1965, Quito

Among the Ecuador capital's enduring architectural legacy is the brutalist Teatro Politecnico, designed in 1965 by Oswaldo de la Torre. The structure's unusual, sculptural concrete volume visually instantly stands out, sitting on a concrete plinth. A glass strip across the facade ensures natural light comes into the building. And while this is a piece of architecture that feels thoroughly modern, at the same time it nods to its pre-Hispanic counterparts with its monumentality and subtly dominating presence. The space inside is still in use as a space for events for the local university. Based on an article that first appeared in the Wallpaper* Summer 2020 issue, written by Hugo Macdonald

Kineta holiday house, 1968, by Alexandros Tombazis

Alexandros Tombazis heads a 60-strong office in Athens and leads about 20 realised and conceptual projects per year. With more than 800 projects under his belt — about 300 of them built — and at least 110 prizes gained in competitions, Tombazis is one of Greece’s most prominent and successful living architects, appreciated more by his peers, perhaps, than by the public. Born in India in 1939, he spent his childhood in Karachi, Tunbridge Wells and London before his family settled in Athens. At the Architectural School of the National Technical University of Athens, he was taught by key figures of the Greek art and design scene — including Nikos Hatzikiriakos-Gikas and surrealist Nikos Engonopoulos — during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Coinciding with the peak of Greek modernism, it was an exciting time. As a student, Tombazis witnessed the global rise of the International Style, and travelled all over Europe visiting innovative buildings such as Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis’ Philips Pavilion, a multimedia showcase, at Brussels’ 1958 World Fair. From this inspirational start, he developed a dedication that has fuelled his tireless productivity, along with a sense of optimism and a belief in the power of technology in architecture. Pictured, here, the Kineta holiday house, designed in 1968 and influenced by the Japanese Metabolist movement, features slim but cleverly insulated concrete walls, using recycled waste from local steel industry furnaces. The bottom right unit is a later addition by the owners.

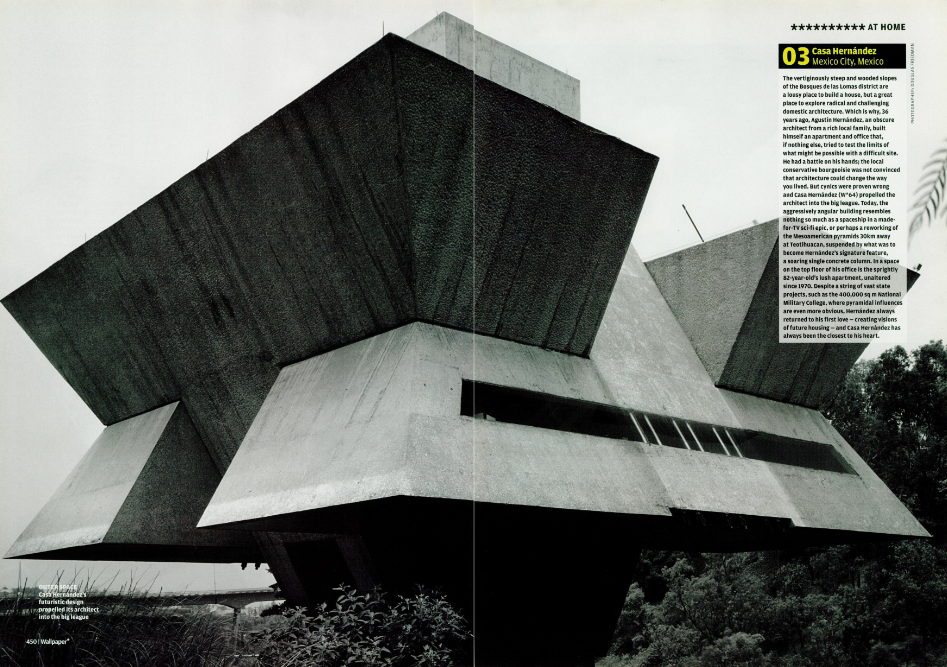

Casa Hernandez, 1970, by Agustin Hernandez

The vertiginously steep and wooded slopes of the Bosques de Ias Lomas district are a lousy place to build a house, but a great place to explore radical and challenging domestic architecture. Which is why, in 1970, Agustin Hermindez, an obscure architect from a local family, built himself an apartment and office that, if nothing else, tried to test the limits of what might be possible with a difficult site. He had a battle on his hands; the local conservative bourgeoisie was not convinced that architecture could change the way you lived. But cynics were proven wrong and Casa Hermindez (W*64) propelled the architect into the big league. Today, the aggressively angular building resembles nothing so much as a spaceship in a madefor-TV sci-fi epic, or perhaps a reworking of the Mesoamerican pyramids 30km away at Teotihuacan, suspended by what was to become Hernandez's signature feature, a soaring single concrete column. In a space on the top floor of his office is the architect's lush apartment, unaltered since the 1970s. Despite a string of vast state projects, such as the 400,000 sq m National Military College, where pyramidal influences are even more obvious, Hernandez always returned to his first love - creating visions of future housing - and Casa Hernandez has always been the closest to his heart. Additional writing: Richard Cook

Sangath, by Balkrishna Doshi

Indian architect Balkrishna Doshi was recently announced as the recipient of the prestigious 2022 Royal Gold Medal for Architecture. The coveted gong has been awarded to the established and widely acclaimed Indian architect through the RIBA and by personal approval by Her Majesty The Queen – it is the UK’s highest architectural honour, announced annually and celebrated around the world by the architecture and design field. Balkrishna Doshi, who also won the 2018 Pritzker Prize and was interviewed in his Ahmedabad home by Wallpaper* in 2009, is one of the world’s most respected architects in his field. Here is the architect’s own studio in Ahmedabad, India, Sangath.

Chapel of Sound, China, by Open Architecture

Nestled in the green, rolling hills of Jinshanling, in the countryside north-east of Beijing, the Chapel of Sound cuts a sculptural, monolithic figure. The project, resembling something between giant land art and a natural rock formation is the brainchild of Chinese architecture studio Open Architecture. The practice, founded by Li Hu and Huang Wenjing, designed the building as an open-air concert hall, offering views to the ruins of the Ming Dynasty-era Great Wall of China, merging its strong, rippling concrete form with its context of greenery and historical architecture. Working with a fairly open brief, the architects described wanting the building to help them ‘see the shape of sound’. The building has a brutalist, almost boulder-like appearance. The material is enriched by an aggregate of local mineral-rich rocks, connecting it physically as well as conceptually with its surroundings. This, the rock-like overall composition, and the fact that the volume was carved to be narrower towards the base (designed with the help of international engineering firm Arup), helped the architects ensure that the piece has a gentler impact in its natural surroundings. At the same time, using no heating or air-conditioning, the Chapel of Sound consumes minimal energy, in keeping with this sustainable approach. Read More

Orientkaj station, Copenhagen by Arup and Cobe

Unlike Paris’ 100 year-old Metro and London’s vast and labrynthine Underground, established way back in 1863, Copenhagen’s transport network is very much a 21st century, work-in-progress project. First opened in 2002, the last two decades have seen the Copenhagen Metro steadily growing, its linear, driver-less, rapid-transport tentacles spreading ever-outwards to the city’s new frontiers. For the recently completed Nordhavn metro line extension, connecting northern docklands to town centre, the city has wisely decided against a generic architectural style with two new stations, Orientkaj and Nordhavn, taking a ‘passenger-focused’ approach that celebrates the character and industrial past of the rapidly developing work and residential area, currently one of the largest urban regenerations in northern Europe. London-based architects Arup and Denmark’s Cobe practice (whose office is actually situated in the Nordhavn district) worked together during a seven year period to conceive two new metro stations – one over ground, one underground – that handsomely reflect the character of the urban areas they serve. Photography courtesy COAST Read More

Beverly Hills house by iDGroup

James Jannard – Jim to his friends – owns a lot of things. He owns several properties in Malibu and in Newport Beach, California. He owns two islands in Fiji, a third in the Pacific Northwest. He also owns a substantial collection of vintage 1980s sunglasses and biking gear. These last two are evidence of something he used to own – the Oakley eyewear brand, which he launched in the 1970s as a maker of motocross equipment, and the sale of which, for $2.1bn in 2007, allowed him to buy many of the other things he owns today. This is a man who knows what he likes, and tends to get it. Jannard has now added another home to his residential options, perched atop a cliff in the chichi Trousdale section of Beverly Hills. The neighbourhood has a standing ordinance forbidding any construction above the first storey, ensuring that the two-acre site has an unobstructed view of nearly the whole Los Angeles basin, from Downtown to the sea. This perch is scarcely less spectacular than the building Jannard has now plonked down on it, an 18,000 sq ft citadel in exposed concrete and aluminium. The house has no official nickname gracing its giant mechanical entry gate; yet the one that suggests itself is cited by both the owner and his architects, iDGroup, as an essential touchstone (so to speak) in developing their brash and brawny scheme: ‘Stonehenge’.

Elma Arts Complex Luxury Hotel, Zichron Ya’akov, Israel

As the evening sun dips behind the Mount Carmel ridge, Sigalit Landau’s colossal marble statue, Thirsty, is thrown into stark relief – barbed shadows dancing across the 26-tonne form of two figures locked in perpetual exertion. Holding fort opposite reception, it’s the opening gambit at Zichron Ya’akov’s Elma Arts Complex, a 95-room hotel founded by art collector and philanthropist Lily Elstein in 2015. It’s one of over 500 works from her archive that grace the grounds, in addition to those part of temporary exhibitions. And while the Jacob Rechter architecture and astonishing location are undoubtedly draws, it’s this array of artwork that is Elma’s raison d’être. It’s an example of the changed fortunes of so-called ‘hotel art’, once seen as little more than background dressing; abstract pieces in sofa-matching colours or hackneyed watercolours of local landmarks. Of course, over the years a specialised industry has emerged, dedicated to the procurement and curation of artwork collections for hospitality – that often rival those of any independent gallery and provide a cultural tether for travellers. Additional writing: Harry Mckinley

AGET Iraklis by Alexandros Tombazis, Athens

On a generous, green site in one of Athens’ smarter northern residential suburbs, a strange concrete presence rises. The long, relatively low structure features unusual, almost retro-futuristic forms, screens that frame large openings and exposed textured concrete that make itclearly stand out from its neighbours. Locals know it well. This is not your typical Greek office building; it is the former headquarters of AGET Iraklis, one of Greece’s best known cement manufacturers. It was designed in 1972 by one of the country’s most celebrated 20th century architects, Alexandros Tombazis (see W*138). The architectural landmark is emblematic of its creator’s style and early explorations of concrete and Metabolist principles, such as the use of modular design and technology – this part of Athens also features his Iliako Chorio (meaning ‘Solar Village’, a 1980s experiment inenvironmental architecture) and his own office. The AGET building was left empty for seven years after the company moved out in 2010, but it has now been given a new lease of life by local architect Georges Batzios. ‘I was on the island of Kythnos for work and the client called me up out of the blue,’ recalls Batzios, who set up his boutique studio in the central Athens neighbourhood of Petralona in 2013, following an international career.

Andes Mountain retreat, Colombia

Concept-led, sculptural concrete architecture, an expansive, wild, native-species garden, and a rural setting with a pleasant climate in a popular destination; there’s plenty to love about this new residential project in rural Colombia, an Andes Mountain retreat by Oslo-based architecture studio LCLA Office and local architect Clara Arango. But it’s the carefully planned harmony of the above elements, the attention to nature, healthy dose of open-mindedness, and can-do attitude of its makers that elevate this project from being a great house, to a truly idyllic retreat. It all started with a commission that landed on the desk of practice directors Luis Callejas and Charlotte Hanson via a friend from Colombia, who is currently based in Mexico and came to them with an enticing, and unusual brief. He wanted to create a domestic base in Colombia, which he could use in the more distant future as a main home, but also make the most of in the meantime, treating it almost as an unofficial artistic retreat. He saw it as a place to get together with friends, but also one to open to creatives visiting the city, to catch up and talk about their global endeavours. It would be offered to artists on an ad hoc, informal basis, if they wanted to stay there for a few days to produce work. ‘What is unusual is that we were commissioned to design a home for the future, not for right now,’ Callejas points out.

Less pavilion, Canberra, Australia

An imposing cluster of slim concrete columns rises amid the ever-evolving landscape of Canberra’s Dairy Road neighbourhood. The area is a formerly industrial part of the Australian capital city, now slowly transforming into a diverse, modern, mixed-use district. One of its latest additions is Less, an architectural pavilion created by developer Molonglo and designed by Chilean architecture studio Pezo von Ellrichshausen. The celebrated and multi-award-winning architecture studio, headed by partners Sofia von Ellrichshausen and Mauricio Pezo, is known for its dramatic, sculptural works – often in its home country of Chile, and in textured concrete – which cut imposing, mesmerising contemporary figures in both urban and natural landscapes. With the new Less pavilion, the architects followed their signature approach, carving a collection of 36 vertical concrete elements and a circular ramp, which leads visitors up to a viewing platform.

MUBE museum, Brazil, by Paulo Mendes da Rocha

Paulo Mendes da Rocha still channels the energy of a revolutionary. The 81-year-old architect’s discourse, usually self-contradictory, is intense, much like the body of work that spans his 50-year career. Take his house in Butanta, for example, which he built in 1964. Even today, it’s an architectural gesture against the culture of individualism. The banishing of circulation space, and the design of rooms with windows that open not externally but internally towards the common areas, represents a radical proposal of respectful co-existence. Delicate paper models all around his office tell stories about his current projects; the Vitória Museum, already under construction; laboratories for Vale do Rio Doce in Belem do Pani; the Vigo University building in Spain; and the new Carriage Museum in Lisbon. The architect seems genuinely unconcerned about the current global economic difficulties. ‘How can Europe talk about crisis aft er having overcome two World Wars and having rebuilt entire countries from scratch? We should allow capitalism to be discussed as well as reinvented,’ he says. Excerpt from an interview with Paolo Mendes da Rocha in 2010. Additional writing: Isabel Martinez Abascal.

World Health Organisation headquarters in Geneva by Jean Tschumi and Berrel Berrel Kräutler

To reach the new addition of the World Health Organisation (WHO) headquarters in Geneva, visitors will need to cross through the entrance of the organisation’s existing, historic building at the end of Appia Avenue. The glazed entrance lobby of the original structure, defined by an intricate structural system on which the tall, pre-stressed concrete volume lies, is suggestive of the building’s modernist value amd brutalist architecture and contributes to the dialogue between old and new. Surrounded by woodland and designed by Jean Tschumi (yet developed posthumously by Pierre Bonnard in 1966), the majestic WHO office building is now being refreshed with an extension by Swiss architecture firm Berrel Berrel Kräutler. The new office building connects to the existing one via a new, underground, elongated plinth – envisioned as the social heart, the ‘agora’, of the entire campus. This gesture further articulates the overall project’s relationship with nature. On ground level, the plinth base becomes a terrace that provides ample vantage points for taking in the surrounding landscape; on the lower ground, it contains a courtyard garden that links and organises the several, different spaces around it. Additional writing: Stamatina Kousidi.

Oscar Niemeyer in Algeria

One afternoon in the British Library, Jason Oddy, photographer, artist and writer, stumbled across some Oscar Niemeyer buildings he was unfamiliar with. The sweeping curves, the volume and the story telling felt familiar, but the location – in Algeria – did not. After further research he discovered that the buildings, two universities and an Olympic-sized sports hall, were largely undocumented. ‘When Niemeyer left Brazil in 1966, after the 1964 military coup, he ended up in Paris, and then in 1968 he travelled to Algiers for the first time. He was there for six years. It’s a long time for an incredibly famous architect to be somewhere, but not that many people are aware of it,’ he tells Wallpaper*. It was in June 1968, that Houari Boumédiène, chairman of Algeria’s Council of Revolution, socialist and hero of the recent War of Independence against France, invited Niemeyer, starchitect of Brasilia (and communist), to ‘project a new vision of Algeria to the outside world, and promote a new generation of engineers and academics.’ Niemeyer got started, designing the University of Constantine, with a sweeping concrete rendition of an open book supported by pilotis for the auditorium, completed in 1975. Then came the University of Science and Technology Houari Boumédiène and the Salle Omnisports known as ‘La Coupole’ for the 1975 Meditteranean Games in Algier’s Olympic Park. Each piece of architecture with their colossal open spaces and grand concrete gestures were designed to reflect Boumedienne’s socialist and militarist principles, and represent an ‘upending of the age-old order’. Pictured here,‘The Village’ VI, University of Science and Technology Houari Boumediene, Bab Ezzouar, Algeria. Additional writing: Harriet Thorpe.

Luna House, Chile by Pezo von Ellrichshausen

Santa Lucia Alto in Chile’s Yungay region, is green and dramatic, filled with dense forests, fertile agricultural plains and tall mountains – part of the Andes starts here. It is also the home turf of renowned, award-winning architecture practice Pezo von Ellrichshausen, headed by Sofía von Ellrichshausen and Mauricio Pezo. And it is here that the dynamic duo embarked upon building their new base, the expansive, combined home and workspace project, Luna House. Exemplifying in one fell swoop the pair’s fascination with form making, exposed concrete and a healthy blend of brutalism and minimalist architecture, Luna House is at once a striking and a calming presence. ‘This is a large and a small building at the foot of the Andes Mountains,’ the architects explain. ‘In fact, it is an aggregate of 12 different buildings separated from each other by visible seismic joints. Saying that this collection of concrete blocks is a house would be too simple.’

Elemental House, Mexico, by Elemental-Alejandro Aravena

With Elemental House, a lucky architecture lover can use their passion to help communities in need. The new-built home is the most recent work by Chilean architecture studio Elemental-Alejandro Aravena, and will be the first prize in a raffle organised by the Mexican philanthropic institution Sorteos Tec to mark the occasion of its 75th anniversary. Proceeds will go towards the charity’s education programmes. 'This house made for Sorteos Tec transforms architectural value into lottery tickets to finance the education of hundreds of young people and improve their quality of life expectations. This ends up producing a common good – something similar to what is done through social housing. That is what one as an architect seeks to achieve all the time: to contribute to the common good through a work,’ says studio founder Alejandro Aravena, winner of the 2016 Pritzker Architecture Prize. Read more

Pa.te.os hotel, Portugal, by Aires Mateus

Portuguese architecture studio Aires Mateus’ most recent love affair with concrete is the new Pa.te.os Hotel – or, ‘patios’, in Portuguese. Set in an untamed part of the Alentejo landscape, the project consists of a series of interconnected courtyard houses overlooking the Atlantic in an oak grove on the hillside of Serra da Grândola. Its concrete forms, like sculptures in the wild, allow the natural surroundings to become part of the architecture. Shapes confidently cut out of the strong concrete volumes mimic the hilly topography of the region, offering look-out points to connect with the land and sea. ‘The ambition of this project is to create a relationship between nature and construction, extending it to the built spaces. We frame, we observe, we select, we grab the landscape,’ the architects said. Read more. Additional writing: Jessica Rose

Path House by Artechnic, Tokyo, Japan

Japanese architecture firm Artechnic has brought a breath of fresh air to a concrete corner of Tokyo. When approached by a family of five to design its new home in Setagaya-Ku, the city’s most densely populated ward, the practice was presented with an opportunity to shake up the neighbourhood’s urban landscape. Exploring the duality between nature and the man-made, the result is Path house: an experiment in form and function. The home’s sculptural make-up takes the guise of a jagged geological formation, masked by a verdant framework of plant life. The coexistence between natural landscapes and architecture was something that Artechnic principle Kotaro Ide sought to evoke through the project. ‘The image of the rocky mountain is burned in my mind after travelling around the architecture of [Peter] Zumthor in Switzerland,’ he states. Read more

Foro Boca by Rojkind Arquitectos in Boca del Río, Veracruz, Mexico

Foro Boca is a concert hall designed to house the Boca del Río philharmonic orchestra which was formed in 2014. With the hall seating 966 people and a rehearsal space for 150 spectators, the Foro Boca sits within a larger regeneration plan for the urban waterfront area at the estuary of the river. Rojkind Arquitectos formed the concrete shape of the building inspired by the forms of the ripraps in the breakwater. Read more

Canopy House by Powell & Glenn, Melbourne, Australia

Inspired by the open-air, concrete architecture of South America, Canopy House sits proud and airy on high ground in a leafy site of Melbourne's Yarra neighbourhood. The architects, Powell & Glenn, founded by Ed Glenn and Allan Powell (and currently led by the former following the latter's retirement), have over the years honed their expertise in creating sophisticated, subtly impactful residences, and this concrete Melbourne home is no exception. Drawing on their client's interest in South American architecture and mindfulness, they created a house that is a carefully choreographed composition of light and space - but which, at the same time, serves the needs of a family lifestyle. The site itself was another key point to consider in the design development, as Glenn explains: 'The site’s cascading topography provided an opportunity to experience the surroundings at multiple levels. At ground level, the thud of the earth is evident, with the progression through the central and upper floors leaving the user floating amongst the tree canopies.' Read more

Morelia garage by Morari Arquitectura

On the outskirts of Morelia, a central Mexican city known for its pink-stone colonial architecture, Morari Arquitectura has designed a new garage for a young tech entrepreneur to make parking up as exhilarating as a ride on his Ducati Scrambler 900. The elongated concrete pavilion with brutalist peaks looks impressively space age but it houses a very earthbound collection of machines. The collection is a personal passion project and includes a sturdy 1980s Jeep CJ-7, a Bentley Continental GT, and a 1969 Ford Mustang Mach 1. And the new garage, designed as a gallery space for private viewings and the owner’s pleasure, combines exhibitionism with functionalism. Morelia-born architect Roberto Ramírez Ochoa, founder of Morari Arquitectura, used the dimensions of a standard car to plan and divide the space into bays, adding an extra car-sized module to house a lobby that is pierced with a dramatic steel staircase leading to an upper-level wellness retreat equipped with a gym, a spa and a massage room. The full version of this article was originally published in the Summer 2020 issue of Wallpaper*

Church at Firminy by Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier's built legacy was extensive, yet his archive of unfulfilled schemes was even more so. One town that reaped more than its fair share of his genius was Firminy, in France 's Loire Valley. In 1953, a determined post-war mayor decided that Firminy, a former mining town, was the perfect blank canvas for Le Corbusier's dreams of a vertical garden city: enter Firminy-Vert. The new town has three complete Le Corbusier works, but plans for a new church laundered as subsequent mayors weren't quite so keen on the brutalist style, and work slowly petered out, leaving an unfinished concrete shell. But thanks to former Le Corbusier apprentice, Jo se Oubrerie, the builders returned on site and the church was completed in 2006. Which is especially exciting because St-Pierre - a geometric composition dominated by a huge concrete cone punctured with slots that will allow light to cascade down into the nave - is only the third religious structure in Le Corbusier 's oeuvre. The full version of this article was originally published in the February 2006 issue of Wallpaper*

The Bijlmermeer Estate, Amsterdam

The Abbot of Bijlmer pads around his sunlit home in a slogan T-shirt and full beard. Most of the disciples who occupy this nine-flat ‘cloister’ in the Kleiburg building have gone for the day, so he can move freely through the communal kitchen to the slender chapel with the cross-shaped window, past full-height glass to the sweeping balcony. Beyond it, children frolic in a quiet common dotted with mature oaks. They’re lucky: this residential complex is one of the loveliest within the controversial social housing project called Bijlmermeer in south-east Amsterdam. At a long wooden dining table, the abbot (real name: Johannes van den Akker) cracks open a bottle of Kleiburg Sicilian white beer, a citrusy blend he brews, like a good Dutch Trappist, in a nearby hangar surrounded by gardens. The microbrewery, which serves enlightened dishes such as sustainable smokedmackerel salad with grapefruit, helps him underwrite the cloister’s expenses and shelter homeless families. A decade ago, the Kleiburg building’s 500 flats were crumbling to their foundations. Developers bought the lot for a single, symbolic euro and hired XVW Architectuur and NL Architects to rescue it. NL’s Kamiel Klaasse says Bijlmermeer had earned a ‘street cred that hadn’t yet filtered to policymakers. Many famous rappers came out of the area, using the buildings and elevated roads in their videos.’ The full version of this article was originally published in the December 2018 issue of Wallpaper*

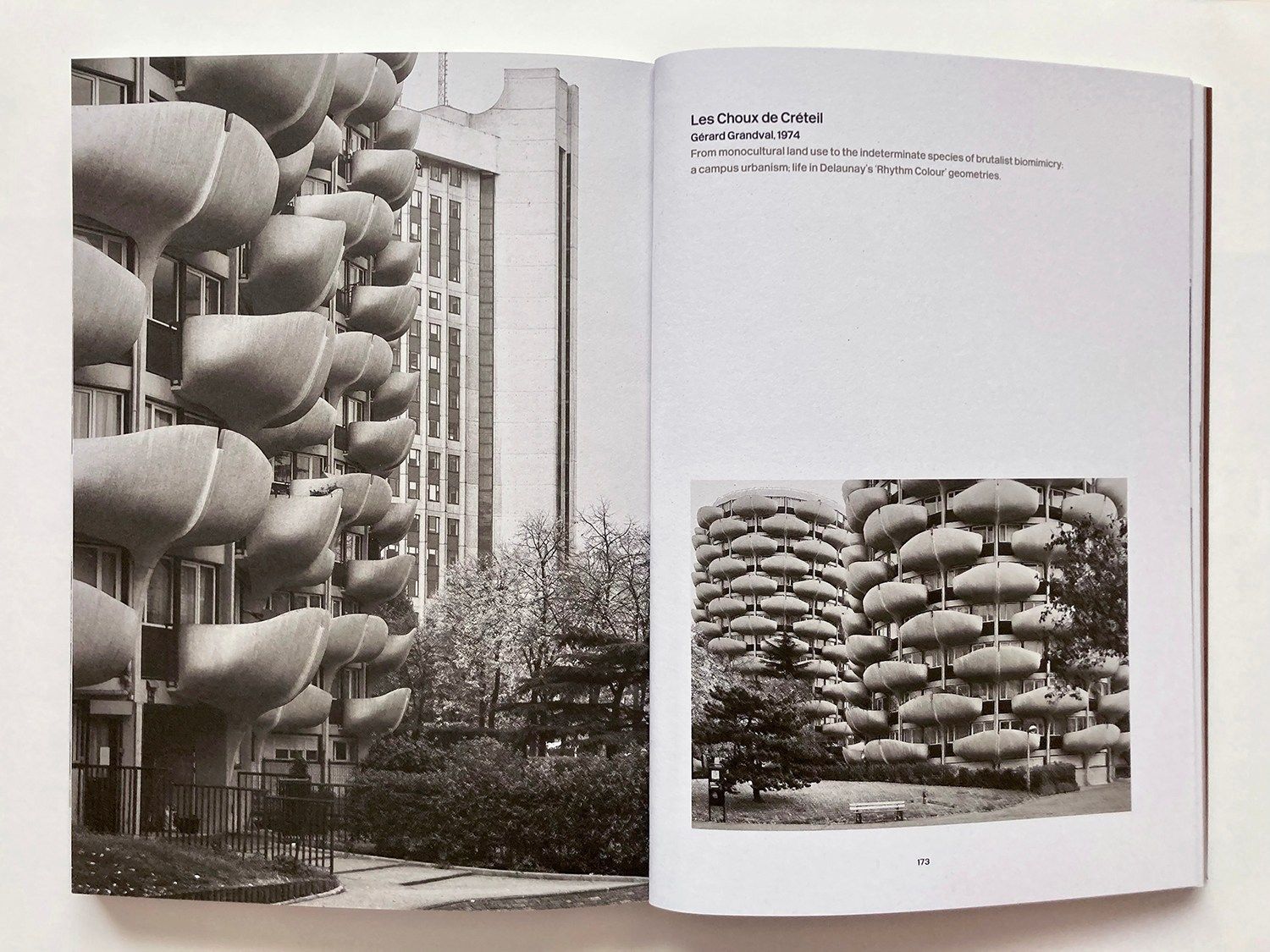

Ivry-Cité du Parc and the Albert Einstein School, Jean Renaudie, Nina Schuch and Serge Renaudie, 1982-83

The photography and essays in Brutalist Paris are underpinned by five years of research into modernist architecture in the French metropolis; they celebrate the city's brutalist architecture, and also make up the first, expansive architecture book from Black Crow Media, long-time specialist in concrete cartography. With photography by Dr Nigel Green of Photolanguage and words by Bartlett associate professor Dr Robin Wilson, Brutalist Paris is very far from being a light-hearted skim over the uncompromising aesthetics of the city’s post-war concrete architecture. Instead, it puts the spotlight on 50 key buildings, connecting them with seven academic essays that look deep into French culture’s relationship with architecture, modernity, and social change. Among the offerings, is Ivry-Cité du Parc and the Albert Einstein School by Jean Renaudie, Nina Schuch and Serge Renaudie, created in 1982-83 and pictured here.

Corpus Christi, Cambridge, by Architects Co-Partnership

This map of modern Cambridge architecture explores more than 40 buildings throughout the British city, touring its rich art deco, brutalist, postmodern and high-tech building heritage. Covering both the local and international architects that have made their mark here, Modern Cambridge Map refocuses our attention, moving it away from the well-documented historic university buildings, and onto more contemporary forms, as well as the city's extensive modernist architecture legacy. ‘You’ll see the city in a whole new light,’ says architecture, design and culture writer Harriet Thorpe, the map's author and a former Wallpaper* staff member. The selection spans from the angular Arup Associates-designed David Attenborough Building to the boxy extensions of the Cambridge School of Architecture and its university housing, designed by Alex Hardy and John Wilson; this is a layered survey of 20th-century design. The space-age Murray Edwards Building, designed by Chamberlain, Powell and Bon, is also included in the map, while injections of colour come from John Outram’s Judge Business School. Elaborate forms and spindly structures can be found courtesy of the Architects Co-Partnership-designed Wolfson-Trinity building and Corpus Christi. Denys Lasdun's Christ’s College New Court offers an intriguingly layered form. The images for the map are taken by artist and photographer Nigel Green, and add visual prompts to Thorpe’s words, letting us explore gems of the built environment with ease, from hidden concrete staircases to fountains and glass roofs.

Casa Alferez by Ludwig Godefroy

The concrete cube of Casa Alferez peeks out somewhat unexpectedly from behind the trees on a woodland plot outside Mexico City. It feels a stark contrast to the natural setting, yet somehow fitting, rising like a monolithic ruin or a futuristic tower in the forest. Its creator, Mexico-based architect Ludwig Godefroy, explains that while its powerful exterior may make a strong statement, it is the result of functional needs. Nothing in this project is random and everything has been carefully planned to fulfil a purpose. Casa Alferez is the weekend retreat of a father and his child, who live and work in the Mexican capital. They got to know Godefroy while he was working on the hotel Casa TO in Puerto Escondido, meeting him through that scheme’s client, and they instantly clicked. The father was already in the process of creating this getaway on a tree-filled site about an hour’s drive from Mexico City (Alferez is the name of the wider region where the project is located).

Trees Sliced Through by Matharoo Associates

The design of this Ahmedabad house was led not only by the brief and lifestyle of its human inhabitants, but by its site's flora too. Trees Sliced Through by Matharoo Associates in the Gujarati city – India's fifth largest – is a case study in working with the existing nature on site, while tackling contemporary forms and modern materials, such as concrete. The result? A home led by its context, which at the same time celebrates a brutalist architecture approach, as well as responds perfectly to the needs of its clients – a young couple expecting children, alongside their parents, and dogs. The project's site was dotted by mature, existing trees – a rare sight in dry and sandy Ahmedabad where, unfortunately, common practice often dictates plots are cleared of trees and vegetation before an architect is approached, the studio explains. At the same time, with a hot arid climate where temperatures can reach up to 48°C, foliage and nature become key in maintaining comfortable living conditions. Matharoo Associates, a studio behind many striking 21st-century homes, including multi-generational structures in Surat and its home town of Ahmedabad, decided early on in the process to make the green context central to its design development.

Star House by Atelier Gratia

Star House takes its name from its site's history, rather than its shape. Located on the fittingly named Star Street in the southern Taiwanese city of Kaohsiung, it also sits on the cross between two urban grids, two planning systems developed during different periods in this urban environment's history, which overlap and find common ground at this point. The result is an angular, loosely star-shaped plot, which lent the home its name. Its architects, the locally based Atelier Gratia, headed by principal Grace Ming-En Chang, enjoyed working with these layers of urban history and playing with this idea of a 'hidden star', which at the same time blends two distinct housing typologies of the region – the row house, and the courtyard house.

Punchbowl Mosque for the Australian Islamic Mission by Candalepas Associates

Sydney’s Candalepas Associates has brought a slice of brutalism to the city’s Punchbowl suburb with an orthogonal new mosque. The concrete structure provides a new home for the Australian Islamic Mission, and its various educative and community facilities can host up to 300 worshippers at once. The mosque forms the first of a two-part project for the local Islamic community. The second stage of the plan will see the development of new community buildings that will orbit the place of worship, in turn bringing the local faith closer together. Candalepas Associates was resultantly driven to give the mosque a unique architectural vernacular, so to help it stand separate and distinct from its future sibling spaces.

Colonnade House by Splinter Society

The beautiful but historical frontage of a period building in Melbourne does not reveal the feast of geometries, concrete brutalist architecture and monochromatic minimalism that unfolds beyond it. This is Colonnade House, the dramatic reimagining of an existing family home, courtesy of local architecture and design studio Splinter Society. ‘Colonnade House emerged from a brief for a large family home that respected, but was distinctly different from, their existing federation home,’ say the architects (federation referring to the style of Australian homes built in the decades either side of 1900). An extension and the complete redesign of the existing space behind the historical front façade have done just that, marking a distinct departure from any period styles and declaring a clean, minimalist presence through a sharp geometric composition, which fully reveals itself on the rear elevation. Meanwhile, a concrete colonnade, which delineates the dining area inside and creates vertical views out towards the garden, lends the house its name. This distinctive feature runs through the side of the extension, adding sculptural architecture and textured surfaces among the owners' carefully placed art collection.

Beelieve school by 3Arquitectura, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico

A school in Mexico has been designed as a concrete circuit to invite people to explore the building. A huge central void in the building opens up a communal courtyard at the heart of the school, while a ramp progresses slowly from the ground floor to the upper levels, allowing people to traverse without a perceptible change in height. As well as concrete, the architects used bricks and wood to create the ‘honest’ aesthetic of the building.

Fishmarket for Hiraki Sawa by Ab Rogers

The origins of this brutalist artist's studio can be found in a Thai festival. The designer Ab Rogers and the artist Hiraki Sawa met at the annual Wonderfruit cultural gathering in Thailand in 2018 and bonded over fish, particularly yellowfin tuna. Both are keen cooks and it got them thinking about cooking, eating and creativity, creative time and space. Sawa, who studied at Slade School of Art under British artist Phyllida Barlow and is best known for short films and collage-base animation, splits his time between London and Kanazawa, where he grew up. In 2019 he took over a raw, empty office space in the Japanese city, initially planning to establish a small co-working space with a business partner. He then changed tack and set on creating something more adventurous and typology-busting, what he calls a ‘co-being’ space.

Concrete Plinth House by DGN Studio

Architects Daniel Goodacre and Geraldine Ng have transformed a dark Victorian semi-detached terrace in East London, into a modern family home that exudes calmness. Grounded on a heavy, concrete base, the home feels at the same time light and sleek. Inspired by brutalist architecture and concrete structures, it features expert joinery and clean, minimalist surfaces anchored in craft, clever material choices and fine detail. The pair set up emerging architecture practice DGN Studio in 2016. They were commissioned by a young couple for this residential project soon after – initially appointed to work just on the home's extension. Soon, they expanded the brief to cover the whole house. ‘Our clients gave us so much to work with,' says Ng. ‘In discussing the brief and project, we found the project was focused less on how it was to look, but how it was to work for the clients. Prioritising function while still factoring form allowed us to select materials that would work in a simple aesthetic harmony, wear beautifully, and ultimately endure.'

Residence FSD by Govaert & Vanhoutte

Residence FSD offers harmony between the manmade and the natural, modernity and a site-specific approach, brutalist concrete and a leafy context. Created by Bruges based architecture studio Govaert & Vanhoutte, the private villa is the primary residence for a family living outside Brussels, and wishing to balance a contemporary home with being close to a more natural environment. Engulfed in its woodland setting, sat just on the edge of a forest, the house feels distinctly modern and minimalist, but it was designed to take its cues from the landscape around it. Nestled in a steep slope, it was shaped by its inclined terrain, with an entrance on the plot's highest point and the main living areas orientated towards the drop and the green views beyond.

Cabo Sports Complex by Taller Hector Barroso in Baja California

A desert site in Baja California Sur plays host to the Cabo Sports Complex – the new home for the Mexican Tennis Open. Designed by Mexico City studio Taller Hector Barroso, the project blends effortlessly the sustainable architecture of earth construction, timber, raw surfaces, and a sense of modernist architecture in a combination that feels entirely fitting for its fascinating, arid landscape. The Cabo Sports Complex site is separated from the beach by the Cabo San Lucas San Jose del Cabo highway. Responding to this, the architecture team conceived the sports complex using elegant, long, compacted earth walls that wrap around the site, protecting it from sun and noise. 'Understanding the meaning of the landscape was crucial for the project. It showed a world where it was possible to create an architecture that, instead of making noise, seeks to remain silent in its context, resting amid the extraordinary natural spectacle we are offered by nature,' the architecture team write.