In memoriam: Balkrishna V Doshi (1927 – 2023)

Balkrishna V Doshi, one of India’s preeminent architects and the world’s greatest modernists, has died at the age of 95. To honour his memory, we revisit a story from the Wallpaper* archives

A glance at the dates and it's clear that Balkrishna V Doshi and modern Indian architecture grew side by side. A student at the JJ School of Art in Mumbai when India celebrated its independence in 1947, the architect's career runs alongside the creation of some of the country's most iconic contemporary architecture. From his involvement in the Chandigarh project and India's famous Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn heritage, through to its finest architecture education institution – he designed and founded the School of Architecture and Planning in Ahmedabad in 1962 – Dr Balkrishna Vithaldas Doshi has been an omnipresent figure for a remarkable period of India's built environment.

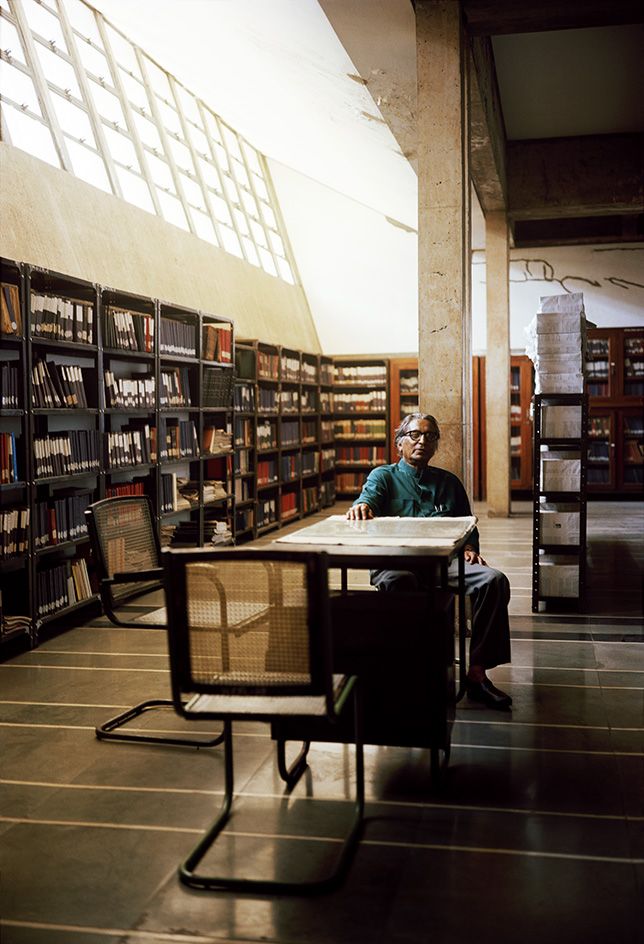

The architect inside the Institute of Indology library in 2011. Doshi built it in 1962 to house thousands of rare Indian books, manuscripts and art

In the words of Balkrishna V Doshi (1927 – 2023)

Having personally had a hand in forming what many people see as modern Indian architecture, Doshi's views about how the country's architecture has shaped and will shape its identity carry weight. His position is very much about the bigger picture. ‘Social identity is Indian identity; we are gregarious people,’ he says. ‘Porosity, change and transformation form the Indian identity. And there is no single aesthetic, as stylistic identity is not a real identity. India is not about a production line, it is not about doing things in a certain way.’

Doshi is adamant about addressing the architectural concerns of contemporary India – from the country's painful inequalities to its infrastructure and sustainability issues. It is all about linking great work, especially on an urban level, to India's wider context. 'How can we place our work on a larger canvas? I think this is our problem; the profession is not addressing issues on a larger scale,' he says. 'This doesn't mean we need to eliminate the individual, but architectural work must make some references to the concerns of the people.'

His practice Vastu-Shilpa, which he founded in 1956 (a research institute and foundation of the same name followed in 1962), certainly reflects this. Set up as a partnership firm, where each partner also has their own projects under the Vastu-Shilpa umbrella, the firm has a dynamic research and urban planning leg that works towards translating cultural and climatic characteristics into appropriate architectural forms from the smaller to the larger scale.

Born in Pune in 1927, Doshi is now well into his eighties, but shows no signs of slowing down. 'I still go to the office every day,' he says, when, that is, he isn't travelling the world attending lectures and conferences. Internationally respected by his peers, Doshi has made his mark as a prolific thinker and teacher, perfecting the application of Le Corbusier's modernist teachings - absorbed during a long stint at the master's Indian office in the 1950s – within the Indian context.

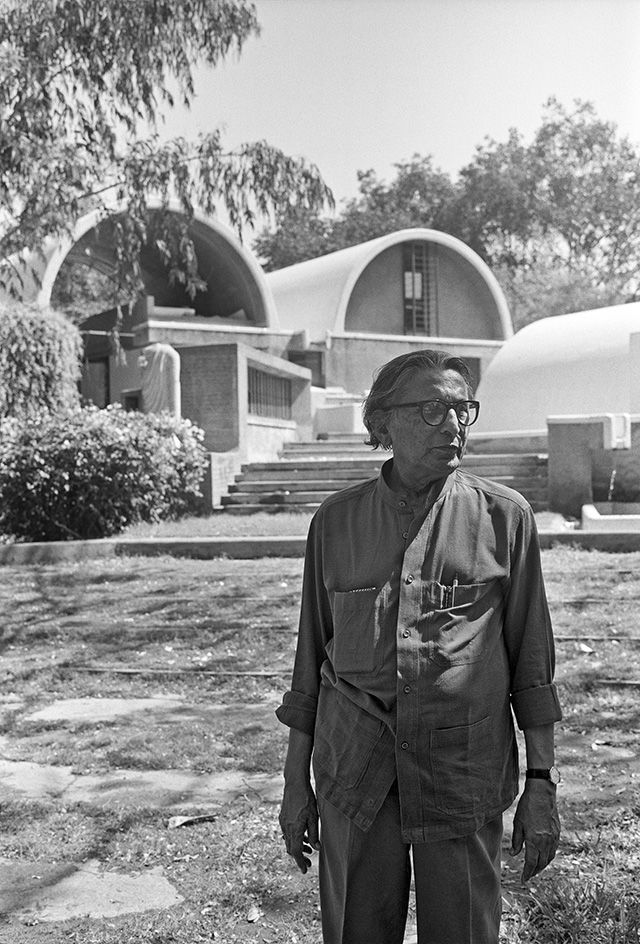

Tagore Memorial Hall

His sense of community in relation to architecture is equally strong. 'I began my career talking about low-cost housing and housing for the poor. This is how one has to work, at the lowest level. Because there is a lot more to learn there. The poor are the ones who are ingenious, frugal, simple, their socioeconomic ties are fantastic,' says Doshi. 'And this is the role of architecture; to be a catalyst for change.'

So where does Indian architecture stand today in relation to the rest of the world? There is no doubt that there is plenty of potential in the country. 'There are opportunities for work here both for the iconic, as well as the barefoot architect,' says Doshi. 'The question is how do these really work in the context of the quality that India stands for.'

The entrance lobby at Tagore Memorial Hall

Globalisation is a further opportunity that India should be well placed to handle, he explains, having itself been born from a melange of cultures, people and traditions over centuries. 'In the past, people were working towards absorbing and finding solutions that were appropriate to the place. That concept should be even more relevant now.'

Perhaps, unsurprisingly, it all comes down to the eternal dilemma of sustainability at all levels. 'It really is the fundamental question that needs to be asked when looking for any local identity. All cultures have talked about this,' says Doshi. 'Our culture is like blotting paper; you don't know which layer has happened when. I think that culture is our strength. Despite diverse languages, diverse climates, diverse traditions, we thrive on our interaction with one another.'

A version of this article was first published in the June 2011 issue of Wallpaper*

Wallpaper* Newsletter

Receive our daily digest of inspiration, escapism and design stories from around the world direct to your inbox

Ellie Stathaki is the Architecture Editor at Wallpaper*. She trained as an architect at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki in Greece and studied architectural history at the Bartlett in London. Now an established journalist, she has been a member of the Wallpaper* team since 2006, visiting buildings across the globe and interviewing leading architects such as Tadao Ando and Rem Koolhaas. Ellie has also taken part in judging panels, moderated events, curated shows and contributed in books, such as The Contemporary House (Thames & Hudson, 2018) and Glenn Sestig Architecture Diary (2020).

-

Snailed it: Jessica McCormack and the Haas Brothers’ playful jewellery

Snailed it: Jessica McCormack and the Haas Brothers’ playful jewelleryJessica McCormack and the Haas Brothers give a second jewellery collaboration a swirl

By Hannah Silver Published

-

Iné in Hampstead is a Japanese restaurant with a contemporary touch

Iné in Hampstead is a Japanese restaurant with a contemporary touchIné in London's Hampstead reflects edomae traditions, offering counter omakase and à la carte dining in a minimalist, contemporary setting

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

Jonathan Baldock’s playful works bring joy to Yorkshire Sculpture Park

Jonathan Baldock’s playful works bring joy to Yorkshire Sculpture ParkJonathan Baldock mischievously considers history and myths in ‘Touch Wood’ at Yorkshire Sculpture Park

By Anne Soward Published

-

House of Greens in India’s Bengaluru is defined by its cascading foliage

House of Greens in India’s Bengaluru is defined by its cascading foliageNestled in Bengaluru’s suburbs, House of Greens by 4site Architects encourages biophilic architecture by creating a pleasantly leafy urban jungle

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Is this the shape of wellness architecture to come?

Is this the shape of wellness architecture to come?Explore the future of wellness architecture through trends and case studies – from a Finnish sauna restaurant to UK cabins and a calming Canadian vet clinic

By Emma O'Kelly Published

-

Surajkund Craft’s Northeast Pavilion in India is an exemplar in bamboo building

Surajkund Craft’s Northeast Pavilion in India is an exemplar in bamboo buildingThe Northeast Pavilion at the Surajkund Craft Fair 2023, designed by atArchitecture, wins Best Use of Bamboo in the Wallpaper* Design Awards 2024

By Ellie Stathaki Published

-

OpenIdeas has designed Link House, an expansive Gujarat family complex

OpenIdeas has designed Link House, an expansive Gujarat family complexLink House accommodates two households in high modern style in the Indian state of Gujarat, innovatively planned around the requirements of a large extended family

By Jonathan Bell Published

-

Restored former US embassy in Oslo brings Eero Saarinen’s vision into the 21st century

Restored former US embassy in Oslo brings Eero Saarinen’s vision into the 21st centuryThe former US embassy in Oslo by Finnish American modernist Eero Saarinen has been restored to its 20th-century glory and transformed for contemporary mixed use

By Giovanna Dunmall Published

-

This Chandigarh home is a meditative sanctuary for multigenerational living

This Chandigarh home is a meditative sanctuary for multigenerational livingResidence 91, by Charged Voids is a Chandigarh home built to maintain the tradition of close family ties

By Tianna Williams Published

-

Discover Dyde House, a lesser known Arthur Erickson gem

Discover Dyde House, a lesser known Arthur Erickson gemDyde House by modernist architect Arthur Erickson is celebrated in a new film, premiered in Canada

By Hadani Ditmars Published

-

Studio Mumbai exhibition at Fondation Cartier explores craft, architecture and ‘making space’

Studio Mumbai exhibition at Fondation Cartier explores craft, architecture and ‘making space’A Studio Mumbai exhibition at Paris’ Fondation Cartier explores the trailblazing Indian practice’s inspired, hands-on approach

By Amy Serafin Published